A new study in the British Medical Journal seeks to decipher the effect of long-term dietary patterns on the microbiome and their subsequent effects on us. Science has found that individual components of food, like fat or sugar, salt or fiber, can enhance or quiet our inflammatory responses, but we seldom eat just fat or sugar. The sum of actions on the microbiome, by whole foods, may be different than the microbiome’s response to food’s parts. This study involved 1425 individuals, a group taken from the general population and a group of individuals with immune-mediated gastrointestinal diseases, ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn’s Disease (CD), and Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS).

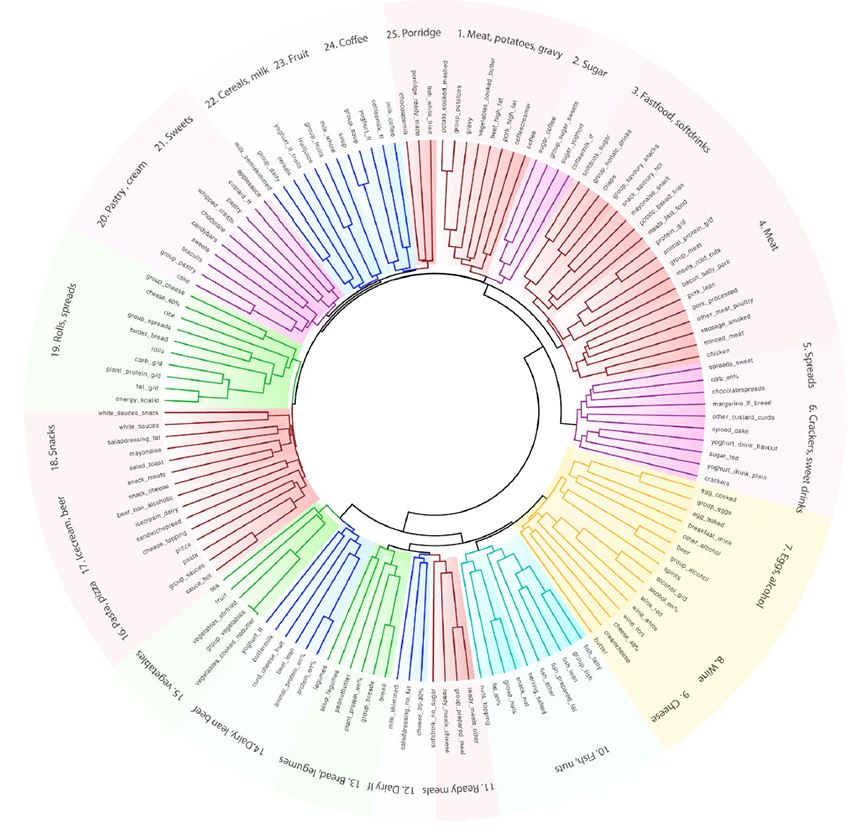

Stool samples from each participant provided data on inflammatory markers, and the type and relative amounts of different microbial species present based upon DNA. Our friend, the food frequency questionnaire, provided the food eaten over the last month; and is a limitation to the causal relationships yet to be described. The dietary data was categorized by nutrients and food groups that “clustered” together, like milk and cereal with milk, meat and potatoes, soup and salad, or a burger and fries. The researchers identified 25 common food pairings, reflective that we rarely eat based on the government guidelines ideal “plate.” [1]

They also grouped the microbiome’s bacteria based upon their species (taxonomy) and functional abundance. [2]

“…we were able to derive dietary patterns that consistently correlate with group of bacteria and functions known to infer mucosal protective and anti-inflammatory effects.”

A few “curated” findings

- “Legumes, breads, fish, and nuts were associated with lower bacterial populations and pathways associated with “the synthesis of endotoxins and inflammatory markers.” These same foods along with fruits, vegetables, and cereals were associated with higher amounts of bacteria “known for their anti-inflammatory effects in the intestine through fermentation of fibre to SCFAs.” SCFAs are short-chain fatty acids found to modulate our immune system and have anti-inflammatory actions.

- “Plant-based food consumption is associated with higher synthesis and conversion of essential nutrients by the gut microbiota.”

- Coffee, tea, red wine, and fruit, all rich in polyphenols, favored anti-inflammatory pathways. Total alcohol and spirits were associated with pro-inflammatory metabolic paths.

- What surrounds protein, i.e., its source, makes a difference. “We consistently observed inverse taxonomical associations of animal and plant foods…”

- “Plant protein was consistently associated with fermentation pathways and the synthesis of anti-inflammatory nutrients…”

- Animal protein often came with higher saturated fats, which promoted species usually more dominant in the upper rather than lower GI tract.

- Plant proteins’ metabolism creates a slightly acidic pH which generally inhibits the “overgrowth” of these upper GI species.

- Fast food, processed meat, soft drinks, and sugar were associated with increasing amounts of Firmicutes – a gram-positive group of bacteria. These bacteria increase “energy harvesting from the diet” [3]. They are associated with other bacterial alterations that eat away at the protective mucous layer lining the gut and increase the ability of bacteria to enter the bloodstream.

In short, your diet affects which bacteria were more prominent than others which in turn altered the microbiome’s metabolic offerings, both pro and anti-inflammatory. This is not settled science. In this study, pro and anti-inflammatory effects were characterized by bacterial species' behavior, not biomarkers. Diet was based upon recall. Finally, while it is believed that these types of “core changes” in bacterial abundance occur over more extended time frames, we have little understanding of the influence of transient dietary change on bacterial abundance.

What does seem clear is that what you eat influences the composition of our gut microbiome, which in turn acts upon us by what nutrients and metabolites they offer up in return. One additional point is worth noting. The effect of animal protein and plant protein was consistently in opposite directions suggesting that they might act, intentionally or not, to balance the microbiome’s behavior. What the optimum ratio between the two is unknown, but for the moment, you might seek the middle way—everything in moderation.

[1] Food groups included alcohol, bread, cheese, dairy, non-alcoholic drinks, nuts, pastry, potatoes, prepared meals, spreads, and vegetables. For those looking on the list for meat, it resides in the nutrient categorization as “animal protein.”

[2] An example might be commensal obligate anaerobes capable of short-chain fatty acid production. Commensal – using food externally supplied rather than eating the host, that would be you and me; obligate anaerobe – an organism that only leaves in an environment lacking oxygen, like our large intestine; short-chain fatty acids are involved in various metabolic pathways and signaling.

[3] The increased “energy harvesting” raises an interesting question. Do fast foods more effectively deliver calories, and if so, is that partially why they increase our weight?

Source: Long-term dietary patterns are associated with pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory

features of the gut microbiome Gut DOI: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322670