Individuals with Type 1 diabetes suffer from a progressive loss of insulin-producing β cells. Insulin therapy is life-saving. In the past, the multiple daily blood glucose tests were managed by algorithms defined on paper – they lacked any customization to the individual’s activity or response to insulin. Today’s Type 1 diabetes management seeks to maintain blood glucose within a set range, typically 70–180 mg/dL, neither too low, hypoglycemia, nor too high, diabetic ketoacidosis.

Hypoglycemia When the glucose is too low, the brain, glucose’s best and primary customer, is impaired. Severe hypoglycemia is so impairing that it requires “external assistance by another person to actively administer carbohydrates, glucagon, or take other corrective actions.” It can result in coma and convulsions. It can result from too much insulin, unplanned or underestimated exercise, and erratic eating. Studies done in the days of the paper algorithm reported rates of severe hypoglycemia in the range of 20–60 episodes per 100 patient years.

Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA) When the glucose is too high, the body breaks down fats, producing ketones as an alternative energy supply. The high glucose levels result in increased urination and dehydration, while the increase in ketones makes the blood more acidic, causing imbalances of electrolytes, primarily potassium, and further impairment of cognition and kidney function. It typically occurs when patients miss doses, experience insulin pump failures, or face increased insulin requirements during stress or illness. DKA has been reported to range from 1 to 8 episodes per 100 patient years.

Both conditions are dangerous and can lead to death. DKA may be a bit more dangerous, although less likely, because its initial symptoms, dehydration, and increased urination may not be recognized as problematic.

The advent of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) in association with an implanted reservoir/pump administering insulin has reduced morbidities associated with diabetes. Open loop systems refer to the combination of CGM and an insulin pump, where the patient is notified and adjusts their insulin dosage. A closed-loop system replaces humans with an algorithm that responds to glucose levels and adjusts insulin dosage in real-time. While the idea of an artificial pancreas has existed since the '60s, closed-loop systems have been deployed since 2016. A new study looks at how they are doing. Perhaps the findings can cut through the hype about AI and medicine to give us a more accurate picture of the benefits and downsides.

The study, published in the Lancet, used a diabetes registry covering nearly all young people with diabetes in Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Luxembourg between January 2021 and December 2023 who used either closed-loop or open-loop insulin therapy for more than a year.

The cohort included nearly 14,000 individuals, median age 13.2 years, slightly more males at 51%, and about evenly divided between open and closed loop systems. The median observation period was a little more than a year and a half, and when weighted, the groups were essentially “identical.”

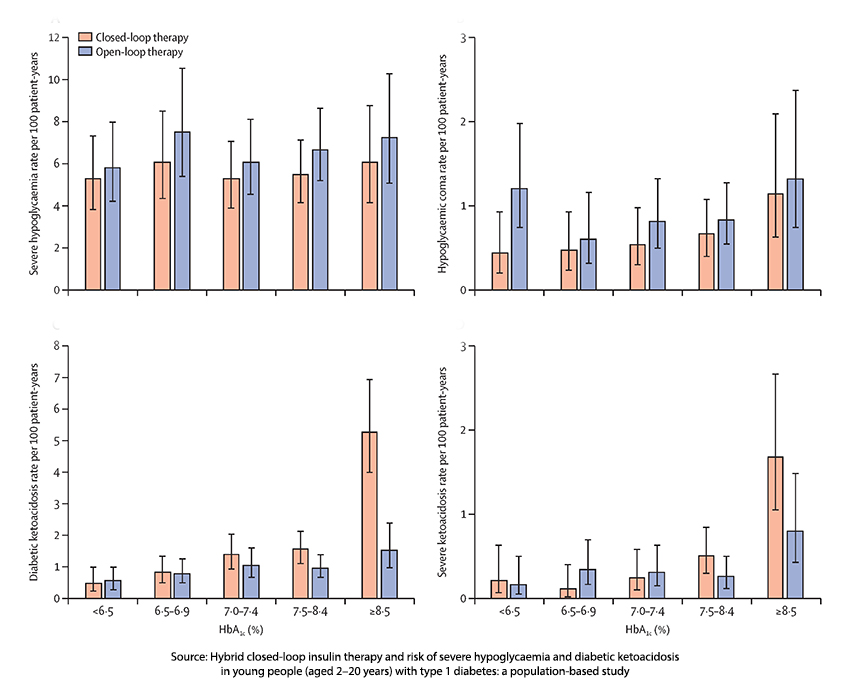

The results are depicted in this graphic.

- With closed-loop therapy, more time was spent within a “tighter” and “looser” target range. Less time was spent above and below those targets with closed-loop therapy, and overall, closed-loop treatment showed less glycemic variability.

- Hypoglycemia was experienced in 5% of the study group, and 1% experienced hypoglycemic coma.

- There was no significant difference in the rates of hypoglycemia between those with an open or closed loop system – about 6 per 100 patient-years.

- Hypoglycemic coma was significantly less in the closed-loop system, 0.62 per 100 patient-years versus 0.91 per 100 patient-years in the open-loop group.

- DKA impacted 1.7% overall, severe events 0.6%

- DKA was significantly greater in the closed-loop group, at 1.74 per 100 patient-years versus 0.96 per 100 patient-years for those with open-loop therapy. There was no difference in the rates for severe DKA

In summary, closed-loop treatment resulted in less hypoglycemic coma, though there was no difference in severe hypoglycemia. It also led to less variability and more time spent within the target range, resulting in a lower HbA1c, which measures chronic glucose levels. However, patients using this algorithm-driven system experience a higher rate of ketoacidosis, particularly for those with higher HbA1c.

This early algorithmic approach to diabetes management does better than the old “standard” guidelines. And it performs better at the lower end of the glycemic spectrum than at the upper end. This may be due to how the algorithm has been written. Perhaps the programmers were more concerned that hypoglycemia, while less frequent, could leave the patient unable to care for themselves or notify others of their condition. Or that DKA, while more common, takes longer to become symptomatic, allowing some margin for it to be detected. As the study’s authors point out, it might be due to equipment malfunction or a “user” error. In the short term, they recommend monitoring for ketones.

Finally, the algorithm could be fine-tuned. Certainly, the logs of closed-loop patients would supply a training set for AI interpretation. In a less litigious society, the patient’s endocrinologist could tweak the algorithm based on the patient’s response. The big step forward has been continuous glucose monitoring, allowing for more flexible insulin dosing and better mimicking of the pancreas. Algorithmic help has been less impactful, and any improvements would require patients to join registries to provide real-world training data for the enhanced pattern matching of machine learning.

Closed-loop therapy is a notable upgrade from past methods, offering tighter glucose control and fewer hypoglycemic comas. However, the trade-off appears to be a higher risk of ketoacidosis, particularly in those with already high HbA1c levels. The algorithms have not yet mastered the problem, and that explains why medicine changes more slowly than the smoke and mirror’s hype demands.

Source: Hybrid closed-loop insulin therapy and risk of severe hypoglycaemia and diabetic ketoacidosis in young people (aged 2–20 years) with type 1 diabetes: a population-based study Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00284-5