As a Boomer, my golden era of music was the late 1960s and early 1970s. My tastes also reach further back to the 1930s, Swing, and the American Songbook. Over the past decade, though, I’ve discovered very few new artists—apart from those introduced during my Peloton workouts. A new study shows that I am not alone in this pattern.

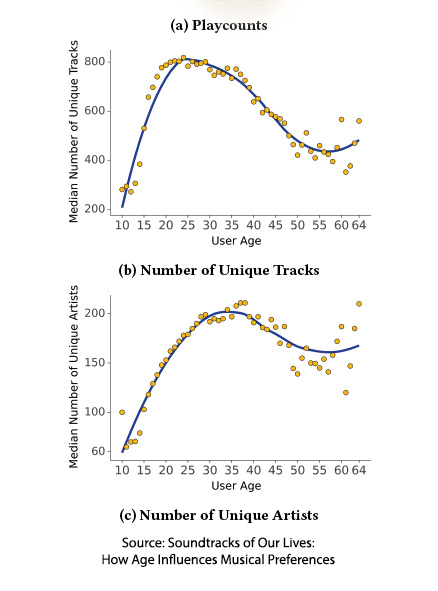

It should be no surprise that our musical preferences shift over time, and earlier studies have found an inverted U-shaped curve that rises, peaks, and falls. In general, our affinity for music created contemporaneously peaks around age 23 and then declines. The diversity of our musical interests continues to widen for two or three more decades and then contracts. For many of us, engagement with music declines as we age.

It should be no surprise that our musical preferences shift over time, and earlier studies have found an inverted U-shaped curve that rises, peaks, and falls. In general, our affinity for music created contemporaneously peaks around age 23 and then declines. The diversity of our musical interests continues to widen for two or three more decades and then contracts. For many of us, engagement with music declines as we age.

In many ways, this description of our changing musical tastes and engagement reflects a time that seems long ago, the era of iPods, when the only curated song lists were found on the radio, and they seemed to be guided by the aesthetics of popularity and payola. This new study looks at what digital curation has wrought by looking at Last.fm, a musical streaming platform. Over 15 years, it tracked the listening habits of 43,000 people aged 10–64, capturing more than half a billion plays across one million tracks.

The researchers considered annual metrics, including the total plays as well as the distinct number of tracks and artists. From that, they found four listening types:

- Super-fans, replaying a small catalog over and over

- Balanced explorers, mixing repeats with discovery

- Serial samplers, trying a track once and moving on

- Casual listeners, with low engagement and narrow tastes

Overall, during our adolescent years, we are intensely engaged in music and active discovery of both new tracks by artists we appreciate and new artists. By the mid-30s, the day-to-day constraints of time and responsibility limit our engagement; we listen less, to fewer tracks, but continue to discover new artists, albeit at a slower pace than our teen years. By late adulthood (>55 years), we may be listening a bit more, but to a refined list of favorites.

The study also measured “artist diversity”—whether listeners sampled broadly or stuck to a few favorites. Teens stream many tracks, but mainly from the current superstars. Our middle years become more diverse, with archival deep dives into artists and genres, as well as “friend-driven” discovery. The artist-based diversity stabilizes in our later years as we tune into a narrow roster of favorites. As we age, we converge on a similarly broad but steady playlist.

The researchers also looked at “song-specific age,” or the listener’s age when a track was released. Youth playlists are dominated by songs from their own time. As listeners grow older, this effect weakens and eventually splits: after 45, playlists often show both a “current” bump and a “nostalgia” bump.

Algorithmic recommendations

Based on their finding, the researchers offered recommendations for improving algorithmically curated playlists.

- For teens and young adults, offer a broad mix—today’s chart-toppers alongside older tracks to encourage exploration.

- For mid-life listeners (25–40), blend the new with the nostalgic, revisiting the soundtrack of youth while keeping current releases in play.

- For older listeners (40+), focus on refined favorites and memory-rich hits, with fewer brand-new songs and more polished personalization.

Music critic Ted Gioia, writing in The Honest Broker, brings the work of these researchers into closer focus as he reports on how algorithmic curation and platform metrics have continued to shape our musical interests. He discusses a survey that sharpens the longitudinal picture of the researchers.

- Even weaker artist attachment among the young.

One of his concerns is the weakening attachment between young listeners and artists. Teens already showed limited diversity, favoring superstars. Now, algorithmic platforms promote “zero-click discovery”—content consumed entirely within the app. Many teens no longer build a relationship with artists at all; they simply enjoy a short clip and move on. - Age 25-34 is emerging as the new tastemaker brand.

By contrast, listeners aged 25–34 are emerging as the new tastemakers. Diversity peaks during these years, when people are most likely to adopt new artists and dig deeply into their catalogs.

For youths, TikTok and Instagram behave like closed gardens; 18 % refuse to leave the feed, and a third forget the song before they can search elsewhere. The platforms underlying attempts to maintain attention trap them in low-diversity, high-turnover loops.

The effect shows up in the data. Teens now rack up billions of “micro-plays”—very short listens on social video—with little follow-up on streaming platforms. Social virality rarely converts to lasting fandom. In short, attention has sped up, loyalty has thinned, and the handoff from viral clip to enduring fan base often happens later in life—if at all.

Zero-click discovery is effortless, removing the “pain point” of a click while simultaneously keeping you firmly attached to the current social media platform, and importantly, it’s advertising. The same pattern is emerging today in web search, where our new AI “pain relievers” put snippets of answers in front of us without the need to click through to the source material. Without reading the source, we rely on AI to be not only accurate but also fair in providing context.

Ted Gioia warns that social media platforms have an “insatiable appetite for content,” anything that gets attention, and that,

“You can’t entrust art forms and creative idioms to these platforms, but somehow they now possess life-or-death control over all of them.”

The impact of algorithmic curation, optimized for attention, ill-understood by its creators in terms of its immediate and downstream implications on music is concerning. The same systems shaping our music also shape our political discourse. Recognizing how they influence musical tastes may give us a clearer, less partisan way to see their effects on culture and politics as a whole.

Source: Listeners Can't Remember the Names of Their Favorite Songs and Artists Ted GIOIA

Soundtracks of Our Lives: How Age Influences Musical Preferences Association for Computing Machinery DOI: 10.1145/3708319.3733673