Addiction as a Chronic Illness: Rethinking Recovery

Roughly 1 in 6 people struggle with alcohol or other substances. More critically, according to the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, over 2 million individuals age 12 or older have alcohol use disorder (AUD), and roughly 8% are receiving treatment. If we expand our consideration to all substances, and I know this is a bit of an apples-to-oranges comparison, the number of individuals impacted rises tenfold, while those in treatment change very little. The traditional barriers to care include stigma, cost, limited specialty capacity, and, in the case of opioid agonist therapy (Buprenorphine), regulations.

Addiction, like asthma or hypertension, behaves more like a chronic illness than a one-time problem. Relapse within a year occurs in about 40–60% of cases, with opioids carrying even higher risk—close to 80%. Yet with sustained treatment, long-term outcomes improve: five years into recovery, as many as 80% of people with AUD can achieve stability.

One underlying reason for the high relapse rate is the triggering relationship between stressors and subsequent substance use; after all, alcohol has been used for centuries as a means of easing social discomfort. In the case of individuals with impaired relationships to substances, those triggering stressors act on our unconscious autonomic system long before an “urge” becomes conscious, making “intentional cognitive strategies” of substance avoidance less impactful.

A Wearable Window into the Nervous System

The steady contractions of our heart have small gaps between beats, with the aggregate being reported as a steady 60 or 70 beats per minute. Heart rate variability (HRV) is the tiny wiggle between successive heartbeats. As our heart rate increases under the sympathetic, fight-or-flight response, the gaps disappear; when the parasympathetic, rest-and-digest response predominates, the heart rate slows, and HRV increases. HRV is a non-invasive biomarker of the balance between the two, with diminishing HRV signaling the presence of a stressor.

Wearable devices, like a smartwatch or fitness tracker, can detect when HRV drops, signaling stress before we consciously notice it. By making the invisible visible, they create an opportunity for timely intervention. In this study, the intervention involved resonance frequency breathing: slow, paced breaths (about six per minute) that strengthen the parasympathetic “rest-and-digest” response.

Putting Wearables to the Test in Addiction Recovery

The study, reported in JAMA Psychiatry, recruited adults aged 18 or older in their first year of a current substance abuse recovery program, randomizing them to treatment as usual or with the addition of a wearable reporting to them, in real time, changes in their heart rate variability. After an eight-week training program, they were asked to wear the device for at least 8 hours a day, and for five minutes, twice a day, practice “resonance frequency breathing. The wearable alerts them of a decreasing HRV, at which time they are asked to practice slow breathing for two minutes.

The study enrolled 112 participants, about 60% of whom were women, with an average age of 46. Most had a severe substance use disorder. Each day, they reported their stress levels, cravings, confidence in staying abstinent, and a range of emotional states. Alongside these self-reports, the wearable tracked HRV, prompted breathing practice, and logged use for real-time remote monitoring.

Participants practice for about 7 of the “required” 10 minutes daily and for about 2 minutes when prompted by the wearable device, indicating that stress had been detected. Overall, adherence to the complete protocol was modest, at around 24%.

Participants practice for about 7 of the “required” 10 minutes daily and for about 2 minutes when prompted by the wearable device, indicating that stress had been detected. Overall, adherence to the complete protocol was modest, at around 24%.

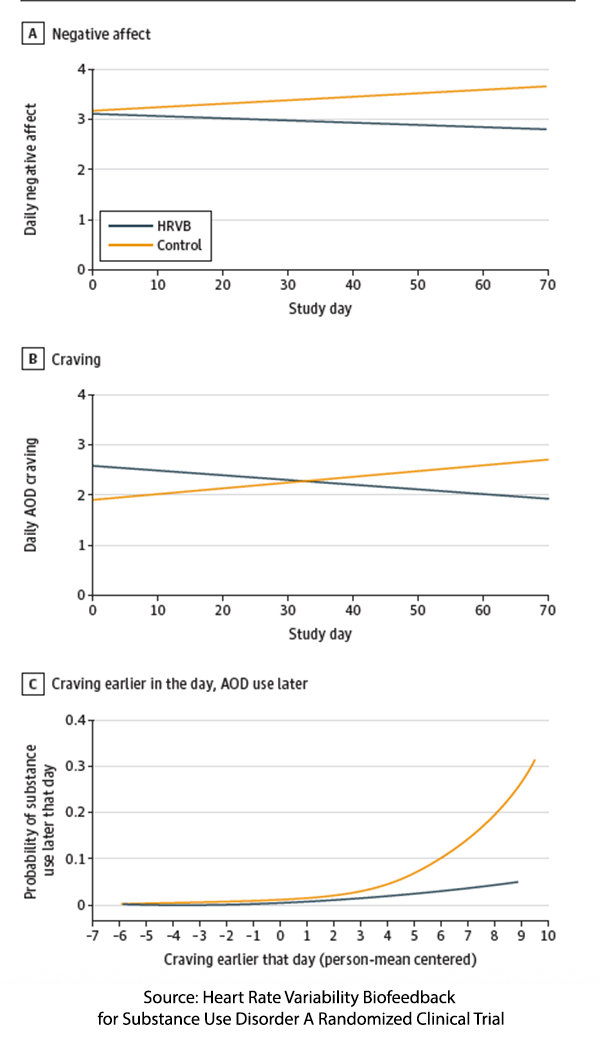

As the graphic to the right indicates, the use of the wearable reduced negative affect and cravings, resulting in a 64% reduction in substance use compared to the control group. There was no effect on positive affect. Moreover, as the lower graph demonstrates, the impact of resonance breathing “decoupled” craving from subsequent use for much, if not all, of the rest of the day. The researchers suggest that “it may matter less how much patients practice overall and more how or when they use this treatment tool.”

What can be measured can be managed

“One of the hallmarks of early addiction recovery is poor self-awareness of emotional states. … People in recovery can experience a lot of stress, but they often don’t have great awareness of it or proactively manage it. ” – David Eddie, PhD, Clinical Psychologist, Recovery Research Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital

By making HRV, a real-time biomarker of stress visible, participants could employ their breathing exercises, resulting in systematic declines in daily negative affect, parallel falls in cravings, and fewer “substance use days.” This is an excellent example of the quantified self—the practice of systematically collecting and analyzing data about one’s own body, behaviors, and environment to gain insights and guide personalized decisions.

From Vulnerable to Manageable

In early recovery, the riskiest moments often occur just before someone uses, when stress and craving escalate too quickly for conscious coping strategies to catch up. By detecting stress in real-time and prompting a breathing exercise, the wearable device interrupts while the risk is still building. It transforms a vulnerable moment into a manageable one, functioning like a digital coach that helps reduce substance use days. To appreciate the device’s value, it is helpful to compare it with other health wearables.

Traditional continuous blood glucose meters (CGM) illustrate the opposite temporal logic of this device, alerting the individual to a high or low blood sugar after the physiologic change has occurred. CGMs are by default reactive, whereas this device, which measures HRV, allows a proactive response.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are an instructive comparison. They alert users after blood sugar has risen or fallen, which makes them reactive rather than proactive. While useful for long-term diabetes care, this timing is less effective against the rapid onset of addictive urges. In contrast, the HRV device shifts the signal upstream—detecting stress before or during a craving. That short critical window of a few minutes can make the difference between managing an urge and relapsing, showing the potential of just-in-time intervention to disrupt the stress → craving → use cycle.

Scaling Research Beyond the Lab

Wearables, as evidenced in this study, open new doors for research in at least three ways:

- Remote-ready recruitment and participation, the portability of smartphones and devices lowers geographic barriers, speeds up enrollment, and makes truly nationwide studies feasible without the need for brick-and-mortar sites.

- Scalable, low-burden study hardware promotes scalability, providing an off-the-shelf tool that can deploy at scale

- Objective data streams remove the burden and variability of self-reports for a host of physiologic data. Moreover, these data streams can provide temporal data, offering unique insights such as the finding that the when of device intervention mattered more than the total practice.

By replacing episodic questionnaires and clinic visits with continuous, real-world data collection, HRV wearables could turn research into a low-cost, living laboratory. This reduces the so-called “voltage effect,” where findings lose impact when scaled beyond the lab. The same advantages also point toward expanded access to care, automating monitoring at scale, allowing both self and remote intervention, reducing disparities in geolocal expertise.

When a physiologic driver of risk can be continuously measured, it becomes actionable. Integrating just-in-time prompts into low-cost wearables turns that measurement into real-world management for stress- and cravings-driven disorders. For people in the highest-risk early months of recovery, an inexpensive wearable that cuts use days by roughly two-thirds and neutralizes cravings' grip—even with limited daily use—constitutes a clinically meaningful signal. While this is not proof of long-term remission, it is a promising signal during a period when traditional treatments often falter. Larger Phase 3 trials tracking outcomes beyond a year, improving engagement, and comparing them against gold-standard treatment, are necessary to confirm whether this benefit holds at scale.

What makes this study compelling is not just the device itself, but the principle it demonstrates. If stress can be measured continuously, it can be interrupted before it cascades into relapse. A wearable that transforms invisible physiological shifts into timely, actionable cues could serve as a low-cost complement to conventional treatment. Still, the findings are preliminary, adherence was modest, and long-term benefits remain unproven. The real test will come from larger trials that track patients beyond the first year of recovery, when relapse risk remains high, and that compare wearables directly against established therapies. If confirmed, this approach could mark a shift from reactive to proactive addiction care. For now, it remains a promising signal rather than a definitive solution.

Source: Heart Rate Variability Biofeedback for Substance Use Disorder A Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Psychiatry DOI: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2025.2700