From Fading Sight to Map-Like Scars: Geographic Atrophy

Any broadcast television viewers have seen the return of Henry Winkler (the Fonz, to the target audience) as spokesman for a treatment for geographic atrophy, a form of age-related macular degeneration.

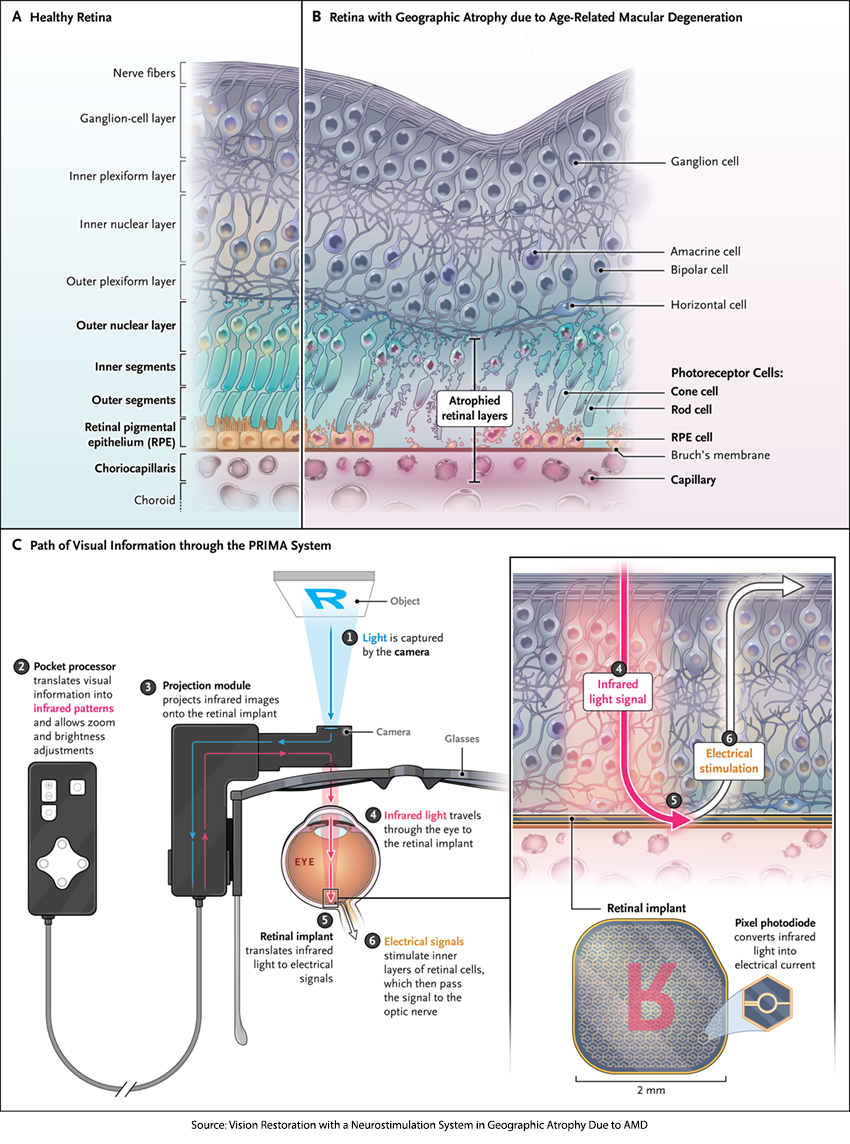

The macula is at the retina’s center — a dense patch of photoreceptors that convert light into the electrical signals our brains interpret as vision. This region gives us sharp central sight and color perception, allowing us to read, recognize faces, and drive. With age, that vital tissue can begin to deteriorate. [1]

A late stage in the process is characterized by sharply demarcated areas of atrophy, the cell death, of those photoreceptors. The map-like appearance of the atrophic patches leads to the term “geographic atrophy” (GA). It impacts roughly 1 million people in the US and accounts for approximately 20% of legal blindness resulting from macular degeneration. The loss of the ability to read and drive is life-altering.

Once the photoreceptor cells die, the vision they provided cannot be restored. GA is a progressive disease, and the only current treatments approved in the US are for medications that slow the progression of the disease while preserving the remaining photoreceptors. Both medicines, given by injection into the eye, interfere with the complement cascade, part of our immune response, which is dysregulated in GA.

Measuring what we see

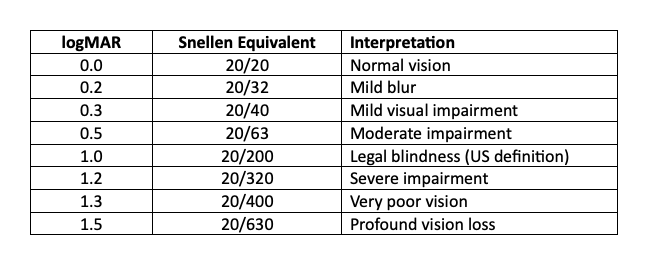

Most of us are familiar with the Snellen Chart as a means of quantifying our ability to see and our visual acuity. The chart compares what we might see at 20 feet to that of a person with normal vision; normal is 20/20, with 20/40, being able to see at 20 feet what a normal person sees at 40 feet, being a mild impairment, and 20/200, the US definition of legal blindness.

Behind the Snellen scores lies a more precise scale called logMAR — the logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution, which measures the smallest distance an individual can resolve. Each line on the eye chart equals 0.1 logMAR. For reference, 20/40 vision equals 0.3, while legal blindness (20/200) equals 1.0. In the following study, an improvement of 0.2 logMAR — about two lines better on the chart — was considered clinically meaningful.

Replacing the Retina: The Birth of Bionic Sight

Replacing the Retina: The Birth of Bionic Sight

A new study in the New England Journal of Medicine reports a very different approach. The PRIMA system creates a cyborg, a human with a mechanical implant. It consists of a camera, invisibly installed into a pair of glasses, that captures authentic world images, processing and projecting them onto an array of sensors implanted beneath the area of retinal atrophy. Those sensors convert projected “near-infrared light” images into electrical impulses stimulating the underlying, still viable, retinal cells, mimicking natural visual signaling and restoring functional central vision. An additional external unit allows the user to adjust the brightness and zoom of the transmitted images. PRIMA is powered by light and is wireless, unlike Neurolink, reducing the concerns about infection.

PRIMA’s theoretical resolution equals about 20/417 vision, which is legally blind but capable of detecting shapes and motion. However, with the glasses’ zoom feature, acuity could improve to roughly 20/42, slightly blurred, but a dramatic leap for someone affected by GA.

The Study

Researchers conducted a multicenter, prospective trial involving 38 participants, with a mean age of 79, bilateral GA, and a baseline visual acuity of 20/320 or worse (≥ 1.2 logMAR). Measurements of visual acuity were made six and 12 months post-implant. Without the device, vision remained unchanged from baseline. However, with the PRIMA system:

94% demonstrated central light perception, and 81% achieved “clinically meaningful improvement” (≥ 0.2 logMAR) at 12 months. The mean improvement was roughly five lines on the Snellen Chart, 0.5 logMAR. In real-world terms, 84% of users could read letters, numbers, or words at home using the prosthetic vision, and 69% reported medium-to-high satisfaction with the system.

Those benefits did come with a cost. Half of the participants experienced a serious adverse effect, all related to surgical implantation. Most occurred and resolved within 2 months of implantation and were manageable with standard ophthalmic care. None were attributed to the device alone. There were no life-threatening events, no device explants, and no participants lost peripheral vision. The data and safety monitoring board concluded that the benefits outweighed the risks and that all observed events were consistent with expected surgical complications.

That safety record gives weight to PRIMA’s early promise and a shift in how we think about treating blindness.

A Transformative Shift from Preservation to Restoration

Geographic atrophy imposes a profound burden on independence and quality of life. The loss of central vision results in loss of autonomy, social isolation, and a growing sense of dependence on caregivers; losses that contribute to anxiety and depression. While the recently approved pharmacologic agents can slow the progression of atrophy, no pharmaceutical therapy can restore lost central vision.

PRIMA neurostimulation offers a fundamentally new approach in this therapeutic landscape: restoration of functional central vision. In practical terms, this technology offers the first real possibility of functional recovery for patients whose daily independence has been eroded by central vision loss.

The Road Ahead: Promise, Peril, and the Meaning of Vision

Despite its promise, the PRIMA system presents practical challenges influencing adoption and accessibility. In addition to surgical complexity and complications, there are issues of cost and access, as well as effectively training users across a range of competencies. Beyond these concerns, long-term effects remain uncertain. Although short-term data show preservation of surrounding tissue and stable peripheral vision, the biologic response to chronic electrical stimulation and foreign-body implantation remains an open question.

[1] The underlying cause of AMD is multifactorial, involving genetics, aging, lifestyle choices, and retinal physiology.

Source: Vision Restoration with a Neurostimulation System in Geographic Atrophy Due to AMD NEJM DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa2501396