She almost didn’t get accepted into the grad school of her choice, rejected by eleven institutions because her GREs weren’t high enough, a recurring pattern of academic disappointments that began in grade school. Yet, in 2009, forty years after she realized the cause of her educational difficulties was dyslexia (the cause of her educational difficulties), Dr. Carol Grieder went on to win the Nobel prize in Physiology or Medicine for co-discovering telomerase, an enzyme intricately involved in the process of aging and cancer development. [1]

Outwitting the aging process seems to be an obsession of some of the planet’s richest denizens these days, some measuring their aging process by their telomerase level.

Introducing Telomerase

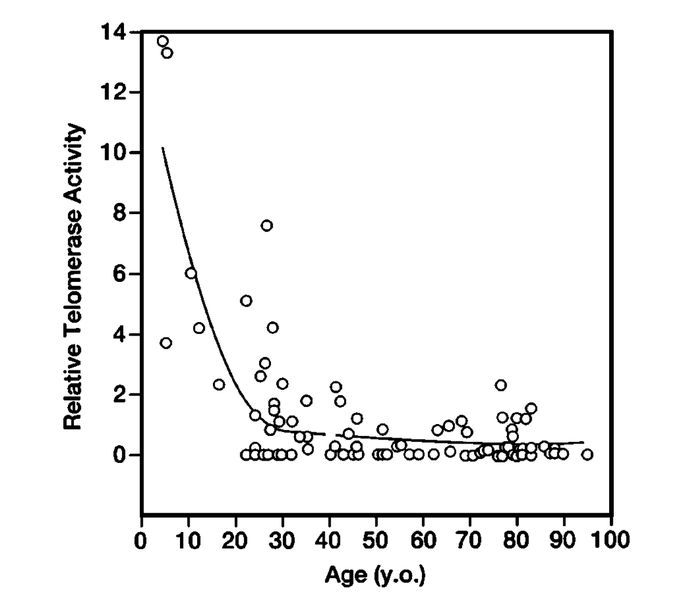

Telomerase is an enzyme that helps maintain the telomeres – structures which lodge at the end of our chromosomes, protecting them, like plastic shoe-lace tips, from insults related to aging and disease. It does this by maintaining the structural integrity of linear DNA during each replication cycle and controlling the lifespan of each cell, thus regulating the aging process. Too little telomerase is a signal your cells are near the end of their lifespan (telomeres shrink as we age, contributing to faster aging). But too much telomerase is not so good either – it signals cancer, the ultimate state of cellular immortality.

Telomerase is an enzyme that helps maintain the telomeres – structures which lodge at the end of our chromosomes, protecting them, like plastic shoe-lace tips, from insults related to aging and disease. It does this by maintaining the structural integrity of linear DNA during each replication cycle and controlling the lifespan of each cell, thus regulating the aging process. Too little telomerase is a signal your cells are near the end of their lifespan (telomeres shrink as we age, contributing to faster aging). But too much telomerase is not so good either – it signals cancer, the ultimate state of cellular immortality.

Measuring telomerase was impossible until 1984, when the enzyme was first discovered by Dr. Grieder, who was a graduate student in the lab of her co-winner, Dr. Elizabeth Blackburn. It took several more months for Dr. Grider to discover its RNA component, and longer still to uncover its role in various diseases. But her academic life wasn’t always easy.

The Life of a Nobel Laureate

Carol Grieder was born in 1961 to academic parents in California, where her father was a physics professor, and her mother a post-doctoral fellow in botany. Her mother died when she was in first grade, an event that she said played an outsized role in developing her independence.

“I was put in remedial spelling classes because I could not sound words out. I remember a special teacher coming into the classroom … to take me out for special spelling lessons. I was very embarrassed to be singled out and removed from class. As a kid, I thought of myself as “stupid”…. It was not until much later that I figured out that I was dyslexic and that my trouble with spelling and sounding out words did not mean I was stupid, but early impressions stuck with me ….” - Carol Grider

When she was ten, she and her brother accompanied their father to Germany, where he had been invited to teach at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics. There, she learned to navigate the public transportation system, a new school, and culture, all while learning a new language. But the schooling experience did not improve, and Carol received Ds and Fs in English assignments. Rejection by her teachers, along with social isolation, led her to form relationships with kids who were “different” and an appreciation of these differences.

“I began to develop an appreciation for people who were not like the others and who stood a bit outside the mainstream [which] served me well later in life.”

By junior high, she began to understand she could be good at school – when she had the freedom to choose classes. But excelling in standardized tests continued to confound her progress, first with low scores in the SATs and then in the GREs, which didn’t match her stellar coursework grades. Nevertheless, her parents’ connections in the academic scientific world opened some doors when she went to select a college (majoring in marine biology at UCSB’s College of Creative Studies). Her GPA and a winning, fun-loving personality fostered strong relationships with her scientific colleagues in graduate school at UC Berkeley, at Cold Spring Harbor Labs, and later at Johns Hopkins, where she rose to become the Director of Molecular Biology and Genetics.

Polygenic Scores, the Perfect Child, and the Downfall of the Human Race

Dyslexia is a language-based learning disability, manifesting in difficulties with language skills, particularly reading, spelling, writing, and pronouncing words. It affects individuals throughout their lives, making it very difficult for a student to succeed academically in the typical instructional environment. Yet Carol prevailed.

She developed compensatory mechanisms, like memorizing, which, along with her love of books, stood her in good stead. But she still had to battle the convention of the “standardized” test, used to select the best of the “standard” applicants, which she failed to master.

Rather than being an obstacle to her success, however, Grieder’s unique perspective seemed to have fostered her scientific accomplishments. In her own words:

"[my] compensatory skills … played a role in my success as a scientist because one has to intuit many different things that are going on at the same time and apply those to a particular problem to not just concentrate on one of them, but to bring many in laterally.”

The Flaws of Pursuing “Perfection “

As commercial labs and some bioethicists continue to champion gene-wide studies to algorithmically calculate risks of various conditions, marketing them to parents seeking the “healthiest child,” it is worthwhile to consider their use in exploring tests that could eliminate dyslexia.

Neurodiversity, something the “best-child” seekers would eliminate, has proved a characteristic of several Nobel luminaries, including Paul Dirac and Barbara McClintock [2], both said to have had autism. Carol Grieder “confesses” to dyslexia, which almost ruined her chances for optimal higher education.

Rather than seeking to eliminate the non-typicals, perhaps the case of Carol Grieder is a reminder that we should embrace those who see things a bit differently.

“If U.C. Berkeley had done the same thing that many of the other schools did, which was to apply a cutoff, then I wouldn’t have gone to graduate school and made the discovery of telomerase and won the Nobel Prize.” – Carol Grieder

Greider’s life is a call to widen the gates of science. When we place value on curiosity and perseverance rather than on neat test metrics, we unlock minds capable of seeing problems from fresh angles. As society debates editing away perceived imperfections (aka differences from the “norm”), Grieder’s life argues for celebrating differences. The next paradigm-shifting insight may be nestled inside a non-standard thinker whose brilliance traditional filters would have missed.

In other words, phooey on those seeking the common-place definition of “perfection.”

[1] “The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2009 was awarded jointly to Elizabeth H. Blackburn, Carol W. Greider, and Jack W. Szostak "for the discovery of how chromosomes are protected by telomeres and the enzyme telomerase.

[2] Barbara McClintock built upon the pioneering telomere research of Herman Muller, who discovered the structure’s existence in flies, finding telomeres in corn in the 1930s.