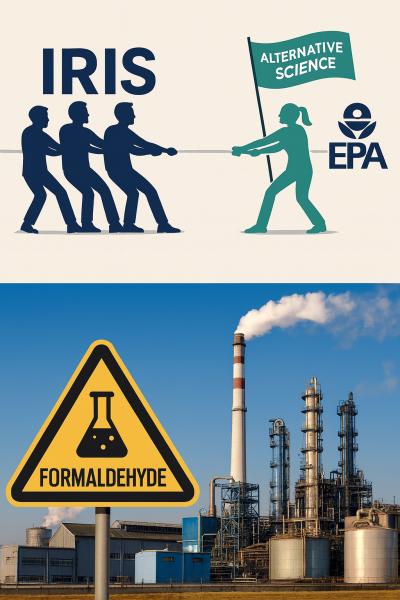

In late December 2024, the Biden Administration went on a midnight spree of proposing or finalizing rules before the Trump Administration took office. One of these actions was finalizing the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) risk evaluation for formaldehyde, a rule based on EPA’s Integrated Risk Information System (IRIS). Unsurprisingly, the Trump Administration’s EPA revised this rule, but what was surprising was the EPA’s bold move of not using IRIS as the basis for its revisions, setting a precedent for future rulemaking.

Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde is a colorless gas that is found everywhere. It is produced naturally by humans, animals, and plants, and is in car exhaust, furnaces, stoves, and forest fires. It is also released into the air from industries that produce or use formaldehyde to make other products such as building materials, pesticides, paints, and adhesives.

Formaldehyde is an essential chemical in the production of essential products in aerospace, agriculture, automotive, building and construction, energy, medicine, national security, science and preservation, and the semiconductor industries. Its market in the U.S. was estimated at $8.39 billion in 2024, driven by increasing demand for construction materials and automotive applications.

What is IRIS?

IRIS is EPA’s database that provides a summary of EPA’s health information for use across the Agency, so everyone within the Agency uses the same data. These data do not have regulatory authority on their own, but are often the basis for EPA regulations, such as the formaldehyde TSCA risk evaluation.

IRIS has caught the attention of Congress. As I discussed previously, legislation was introduced in February 2025 that would prohibit the EPA from using IRIS assessments for rulemaking or other regulatory actions. Some members of Congress believe that IRIS is way too powerful for a program not authorized by Congress and not subject to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA), which requires agencies to publish proposed rules in the Federal Register and accept public comment.

“Chemistry is the driving force behind American innovation. … The IRIS program has a troubling history of being out of step with the best available science and methods, lacking transparency, and being unresponsive to peer review and stakeholder recommendations. As a result, the IRIS program—which has never been authorized by Congress—produces assessments that defy common sense.”

- Chris Jahn, President and CEO of the American Chemistry Council

EPA has a long, tortured history with its IRIS formaldehyde document. It released its first draft in 2010, completed its “new” draft in 2017, which was “suspended” in 2018, “unsuspended and revised in 2021 and 2022. This is the version used as the basis for the “Biden” TSCA risk evaluation for formaldehyde.

The EPA’s Science Advisory Committee on Chemicals (SACC) raised two major concerns.

- Noncancer: The studies selected in IRIS to set the benchmark for formaldehyde were respiratory-system studies (pulmonary function and asthma) that had severe limitations, such as confounding variables that make it difficult to assign causation to formaldehyde.

- Cancer: IRIS concluded that formaldehyde exposure resulted in nasopharyngeal cancer, sinonasal cancer, and myeloid leukemia, and calculated a cancer risk based on the non-threshold model of cancer.

The SACC recommended that, for noncancer studies, the EPA use controlled short-term human studies on sensory irritation to set the benchmark, which would be protective against all other effects of formaldehyde. For the cancer-related studies, SACC cited a recent meta-analysis that examined 16 epidemiological studies and four animal experiments and found that the data do not demonstrate a causal relationship between formaldehyde and blood cancers. They also said that the cancer risk should have been assessed using a threshold model.

Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA) Risk Evaluation for Formaldehyde

Under TSCA, in the waning days of the Biden Administration, the EPA published a final risk evaluation for formaldehyde, determining that:

“Formaldehyde presented an unreasonable risk of injury to human health, specifically to workers and consumers, under its conditions of use.” [emphasis added]

The unreasonable risks are due to eye irritation and respiratory inflammation from short-term exposures and a risk of cancer from long-term exposure of workers [1]. On December 3rd of this year, the EPA released an Updated Risk Calculation Memorandum for Formaldehyde. While leaving the previous determination that formaldehyde presents an unreasonable risk of injury to human health intact, it provides regulatory relief to several industries, for five specific worker conditions of use and three occupational non-user scenarios where there is no longer an unreasonable risk from inhalation alone. Because of the continued risk from skin exposure to formaldehyde, the EPA left the overall unreasonable risk determination in place.

However, the most significant change is that the EPA did not use the benchmarks in IRIS; instead, they calculated a new value for short-term sensory irritation, as recommended by the SACC. [2] This is long overdue because the IRIS program often uses outdated data and opens the door to political bias rather than current science as the benchmarks.

Moving forward, there seem to be three choices regarding IRIS.

- Reform IRIS, requiring better data and more peer review. This seems unlikely because IRIS has become a political football with competing interests that make reform unlikely.

- Eliminate IRIS: This could occur if Congress passes the recently introduced “No IRIS Act” or if the EPA Administrator eliminates the program. It too is unlikely. Congress will not act in an election year; however, the Administration may eliminate IRIS as part of the extensive reorganization currently underway at the EPA.

- Use alternative data: EPA offices could use data outside IRIS in developing rules and regulations, as was done in the formaldehyde TSCA risk evaluation.

This should not be about political philosophies; it is about finding the best scientific data to make important decisions about chemicals like formaldehyde.

The real story here isn’t partisan whiplash—it’s whether EPA will finally anchor major chemical decisions to the best available, most transparent science rather than defaulting to an opaque program with a checkered track record. Formaldehyde’s revised TSCA evaluation demonstrates a practical path forward: use rigorous, fit-for-purpose evidence (like controlled human sensory-irritation studies) when it better reflects real-world biology and exposure, while still protecting workers and consumers. By choosing higher-quality data now, the Agency can make rules that are both scientifically credible and operationally workable, precisely the kind of precedent regulatory science has needed.

[1] Virtually all conditions of use contributed to the unreasonable risk determination, including manufacturing, processing, incorporation into materials such as textiles, rubber, and construction materials, and use in fuels, lubricants, and laboratory chemicals.

[2] They stated that since formaldehyde effects are limited to the site of contact (the eyes and nose) and do not accumulate in the body, the short-term value should be protective against other health effects, including cancer.