Body mass index (BMI) has been the dominant method for classifying obesity for more than half a century. It is an easy calculation, simple to deploy at scale (pun intended), based on one's weight and height - BMI = (weight in kg) / height in meters)2) making it useful for population-level surveillance. However, as researchers have repeatedly pointed out, it was never designed to assess health risk in individuals—a distinction that matters in clinical care, employment screening, and fitness-for-duty decisions.

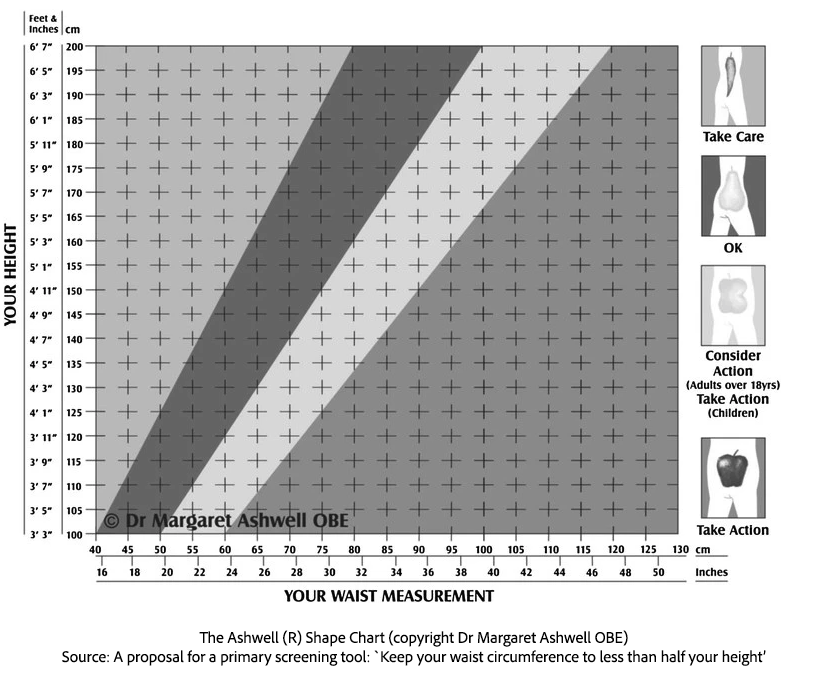

Among the most prominent voices highlighting this gap is Dr Margaret Ashwell OBE, former president of the UK Association for Nutrition, whose work has consistently shown that where fat is stored may matter more for health risk than total body weight alone.

BMI and mortality don’t align as well as we thought

In a 2014 analysis, Ashwell and colleagues revisited data from the UK Health and Lifestyle Survey, a cohort originally recruited in the mid-1980s, similar to the US NHANES annual surveys. Using records with approximately 20 years of follow-up, they showed that the waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) was more strongly associated with mortality risk and years of life lost than BMI.

This work built on earlier studies and reviews showing that WHtR correlates more closely than BMI with cardiometabolic risk factors, including elevated cholesterol and type 2 diabetes, reflecting the greater metabolic activity of abdominal fat compared with fat distributed elsewhere in the body.

The public-health message that emerged was simple and memorable:

“Keep your waist circumference to less than half your height.”

The authors suggested that incorporating WHtR into routine screening could “add years to life.” Yet despite the clarity of the message, BMI remained entrenched in clinical and policy settings.

New large-scale confirmation

Fast-forward to the 2020s, and the evidence base has only strengthened. A landmark analysis published in the International Journal of Obesity towards the end of last year examined data from over 120,000 individuals drawn from the Health Survey for England between 2005 and 2021.

The findings echoed and extended earlier research. Measures of central obesity, including waist circumference, waist-to-hip ratio, and particularly waist-to-height ratio, consistently outperformed BMI in identifying individuals at elevated cardiometabolic risk. Importantly for real-world screening, the researchers showed that BMI would misclassify a substantial proportion of the population. Some individuals labelled with “healthy weight” by BMI fell into high-risk categories once abdominal fat was taken into account. In contrast, others with higher BMI but greater muscle mass were flagged as high risk despite lower central adiposity.

These limitations to BMI became more pronounced with age, as muscle mass declines and fat distribution shifts; BMI becomes a progressively weaker proxy for health risk—a key issue in ageing populations. By contrast, waist-based measures, especially WHtR, tracked risk more consistently across the life course, aligning better with what is known about age-related cardiometabolic disease.

The gap between evidence and practice

Despite this growing body of evidence, BMI remains widely used as a standalone metric in clinical practice, public health, and eligibility decisions—including insurance underwriting and occupational fitness standards. However, the gap between evidence and practice is beginning to narrow—a change not of the science, but its uptake.

In a notable shift, the US Department of War has announced a new system for assessing body composition in military personnel, replacing traditional height-and-weight tables with a waist-to-height ratio standard. Under the new rules, service members must maintain a WHtR below 0.55, alongside sex-specific body-fat percentage thresholds.

Those exceeding limits will be enrolled in corrective physical training programs, with repeated failures potentially affecting promotion or continued service. Assessments will take place twice yearly across all branches.

From a policy perspective, this move is significant. Military organisations have strong incentives to prioritise functional health and performance over crude weight measures. That the Pentagon has chosen WHtR reflects growing recognition that central obesity, not body weight alone, which may be elevated in well-muscled individuals, is more closely linked to long-term health, injury risk, and operational readiness.

Why change has been slow

BMI’s persistence is not hard to explain. It is cheap, fast, and requires no training beyond using a pocket calculator. Waist measurements, by contrast, introduce practical questions: where exactly to measure, how tightly to pull the tape, and how to standardise technique. [1]

But these are solvable problems, and modest ones compared with the cost of misclassification. As Ashwell has noted repeatedly, WHtR combines simplicity with biological relevance. A tape measure can often convey more actionable information than a scale alone.

Where BMI still fits—and where it doesn’t

None of this means BMI is useless. As researchers continue to emphasise, it remains valuable for monitoring trends at a population level. On average, BMI performs reasonably well.

The problem arises when BMI is used as a diagnostic shortcut for individuals, particularly older adults, athletes, or those with atypical body composition. In those cases, reliance on BMI alone risks both false reassurance and unnecessary alarm—with potential downstream effects on clinical decisions, insurance status, and employment eligibility.

A metric ahead of its time

That waist-to-height ratio has taken more than 30 years to gain traction, says less about the evidence than about institutional inertia. With mounting data, clearer public messaging, and now high-profile adoption by organisations such as the US military, WHtR may finally be moving from “interesting alternative” to a routine tool.

If that happens, it will not represent a radical new idea—but the delayed acceptance of one that has been hiding in plain sight.

[1] Measure just above the belly button and have the tape snug but not tight.