A new meta-analysis upends the belief that red meat is bad and vegetables are good. How can that be? It begins by reassessing how researchers “weigh” the impact and uncertainty of the studies they consider.

The researchers, reporting in Nature Medicine, begin here.

“Exposure to risks throughout life results in a wide variety of outcomes. Objectively judging the relative impact of these risks on personal and population health is fundamental to individual survival and societal prosperity. Existing mechanisms to quantify and rank the magnitude of these myriad effects and the uncertainty in their estimation are largely subjective…”

There is any number of reasons that meta-analysis, the aggregation of many studies, might be uncertain, including the choices of studies to report, the size of those studies, along with the specific characteristics of the population and outcomes considered. At best, meta-analysis considers a wide variety of apples and, at worst, apples and oranges. The research contribution is a new methodology to reduce uncertainty and bias.

The Burden of Proof Risk Function (BPRF)

“[BPRF] is a reflection of both the magnitude of the risk and the extent of the uncertainty….”

The underlying mathematical techniques are offered as a “complimentary” technique to those already in hand. It takes the mean risk of an outcome, measured by looking at the response of the middle 15% to 85% of respondents, thus eliminating the extremes or “outliers.” It then characterizes that outcome as the “smallest level of excess risk that is consistent with the data” – they interpret the data conservatively. More importantly, it does not assume the linear nature of the risk, modifying the argument that the “dose makes the poison,” acknowledging that a particular risk might plateau and cause no further deleterious effects or even a small amount might not be harmful, but helpful. (You can read more about linear “thresholds” in biological systems here.)

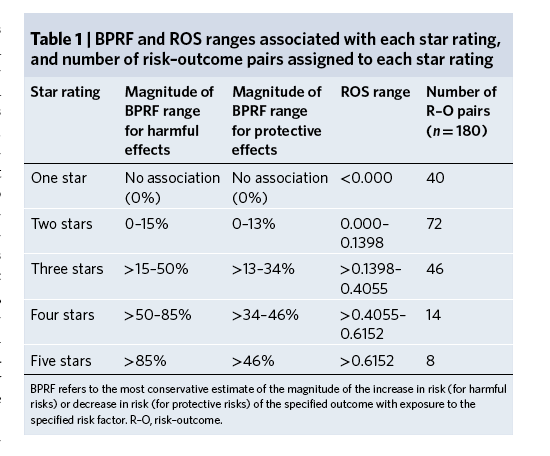

They assigned stars to their findings to make their work more accessible to non-experts. One and two stars indicate that “conservative interpretation of the evidence may suggest” no or weak evidence of a protective effect to five stars where there was solid evidence of a protective effect of more than 46%. To demonstrate the methodology, they considered four risk factors, smoking, hypertension, and consumption of red meat and vegetables, along with various outcomes, creating 180 risk-outcome (R-O) pairs. Here is what they found.

They assigned stars to their findings to make their work more accessible to non-experts. One and two stars indicate that “conservative interpretation of the evidence may suggest” no or weak evidence of a protective effect to five stars where there was solid evidence of a protective effect of more than 46%. To demonstrate the methodology, they considered four risk factors, smoking, hypertension, and consumption of red meat and vegetables, along with various outcomes, creating 180 risk-outcome (R-O) pairs. Here is what they found.

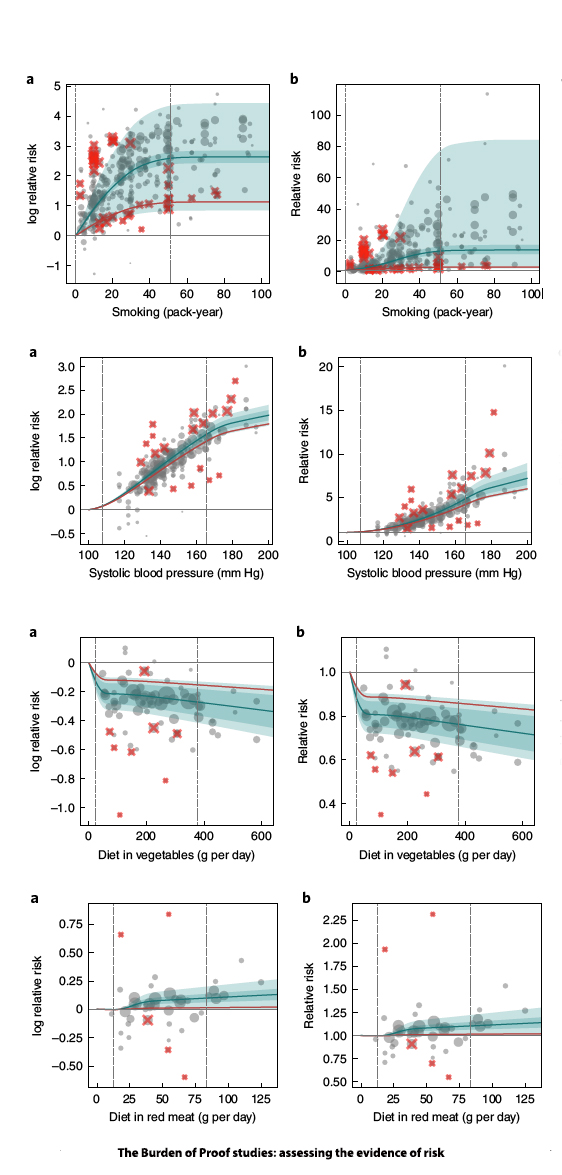

Each graph demonstrates the studies considered and their outcomes along with the derived BPRF, with the shaded areas representing the uncertainty of their conclusions.  Both charts show relative risk or benefit; the one to the left has a logarithmic scale.

Both charts show relative risk or benefit; the one to the left has a logarithmic scale.

Smoking – 371 observations from 78 studies since 1980. “On average, we found a very strong relationship between pack-years of smoking and log relative risk of lung cancer…smoking dramatically increases the risk of lung cancer.” 5-star risk-outcome pair

Hypertension – 189 observations among 41 studies involving systolic blood pressure and ischemic heart disease. 5-star risk-outcome pair.

Heart Disease and Vegetable Consumption – 78 observations from 17 studies. “The relationship is not log-linear. We found that, on average, vegetable consumption was protective, with the relative risk of ischemic heart disease being 0.81 (0.74–0.89) at 100 grams per day vegetable consumption compared to 0 grams per day.” The calculated BPRF suggests a lower risk of heart disease of roughly 12%. 2-star risk-outcome pair.

Heart Disease and Red Meat Consumption – 43 observations from 11 studies. “For unprocessed red meat and ischemic heart disease, the exposure-averaged BPRF is 0.01, essentially on the null threshold.” The calculated BPRF suggests a lower risk of heart disease of 1%. 2-star risk-outcome pair. (I think this might still be too generous, but that is my bias.)

Nearly two-thirds of the outcomes were ranked one or two stars; just 22 were ranked four or five stars. They pointed out that some risks, like smoking and hypertension, had high star ratings for multiple outcomes, “which should be considered when making individual decisions around risk exposure.” And while one-star ratings can receive less attention, there may be “small but meaningful benefits for individuals if their exposure is reduced.”

Personal vs. Public health

While the star rankings are intended for the non-experts, the researchers believe they serve a complementary and valuable purpose to experts with a more nuanced and “inherently subjective” understanding. The researchers fall back on two risk assumptions in the public health arena.

- “The precautionary principle implies that public policy should pay attention to all potential risks.”

- “…public policy should pay attention not only to the risk functions that are supported by evidence but the prevalence of exposure to those risks.”

Your personal decision regarding these risks should likewise be based on the prevalence of your exposure and your risk tolerance. It would be stupid to ignore those five-star risks, but for the one and two-star risks, a bit of moderation, especially in the dietary choices, might serve you just as well.

The editorial accompanying this study makes two points limiting this or any other meta-analysis. First, it does not solve the bias within studies that use “lifestyle questionnaires for recording risk factors and self-reporting of health outcomes.” Second, many of these studies come from “well-resourced” areas, i.e., first-world countries, and may not be generalizable globally. This is equally true for the applicability of extensive “third-world” studies to “first-world” countries.

Last word from the authors,

“One of the goals of this new star rating system is to clear up confusion and help consumers make informed decisions about diet, exercise, and other activities that can affect their long-term health.”

- Dr. Christopher Murray, Director of the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

For those interested in all of their findings, they have provided the data in an easily visualized manner here.

Source: The Burden of Proof studies: assessing the evidence of risk Nature Medicine DOI: 10.1038/s41591-022-01973-2