The stereotypical surgeon requires a deft hand and a cool demeanor. However, in the hospital ecosystem, manual dexterity is crucial in many roles, including those of interventionalists (such as cardiologists and radiologists), hospitalists, nurses, and non-clinical staff. A tongue firmly in cheek study reported in the BMJ asks, given these diverse roles, “whether people wielding scalpels truly possess greater dexterity than people in other hospital staff roles.”

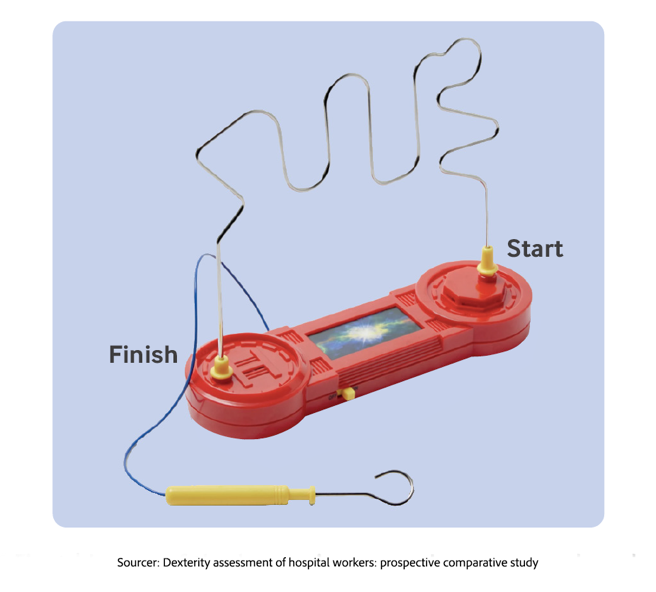

Common sense suggests the answer is yes. But our intrepid researchers sought to address the “evidence gap” by testing the dexterity of some of their co-workers. Dexterity was measured using a “a twisted metal wire path fixed on a non-conductive base,” where participants guided a metal loop from one end to the other—touching the twisted path with the loop set off a buzzer, with the goal of completing the entire path without triggering it.

Common sense suggests the answer is yes. But our intrepid researchers sought to address the “evidence gap” by testing the dexterity of some of their co-workers. Dexterity was measured using a “a twisted metal wire path fixed on a non-conductive base,” where participants guided a metal loop from one end to the other—touching the twisted path with the loop set off a buzzer, with the goal of completing the entire path without triggering it.

While the primary outcome was successful completion of the course in under five minutes, researchers also captured the secondary outcomes of attendant swearing and expressions of frustration as participants navigated the path.

A total of 254 hospital staff members participated in the study, comprising 60 physicians, 64 surgeons, 69 nurses, and 61 non-clinical staff members. Nurses were younger than physicians, surgeons, and non-clinical staff, at 38 years. Gender distribution was stereotypical, with the majority of physicians and surgeons being men, while nurses and non-clinical staff were predominantly women.

WTF?

Dexterity Assessment – 84% of surgeons had a significantly higher success rate in completing the buzz wire game within five minutes compared to roughly 50% in each of the other groupings. Surgeons completed the task substantially more quickly than other groups, and the observations remained unchanged when accounting for age or gender. Surgeons had the fastest median time to game completion or failure at 89 seconds, while the “thinking” physicians took 2 minutes. Nurses were a bit more hesitant, as were the non-clinical staff.

Swearing and Noises of Frustration The 64 surgeons exhibited the highest rate of swearing, 50%, during the game, significantly higher than that of the other groups. Unsurprisingly, among physicians who have crossed a nurse, nurses had the second-highest rate at 30%. Non-clinical staff showed the highest use of frustration noises at 75%, followed by nurses, surgeons, and physicians.

Cooping Mechanism

While it is often a classic description of the work of an anesthesiologist, it might apply equally well to surgeons – “hours of boredom, interspersed with moments of terror.” As the researchers point out, the propensity “for swearing might be a coping mechanism for high-pressure situations to help them maintain skill despite stress.”

A meta-analysis found that excessive surgical stress impairs performance, intraoperative communication, and decision-making. A study in a general population of Pakistanis found that those who were more profane had less stress, anxiety, and depression. From the point of view of the rest of the operation room staff, this may reflect the downside of the aphorism that it is better to give (profanity) than receive.

The researchers end by suggesting “a swear jar or similar intervention aimed at reducing swearing and optimising composure…” Why they would deny a surgeon their moment eludes me.

Source: Dexterity assessment of hospital workers: prospective comparative study BMJ DOI: 10.1136/bmj-2024-081814