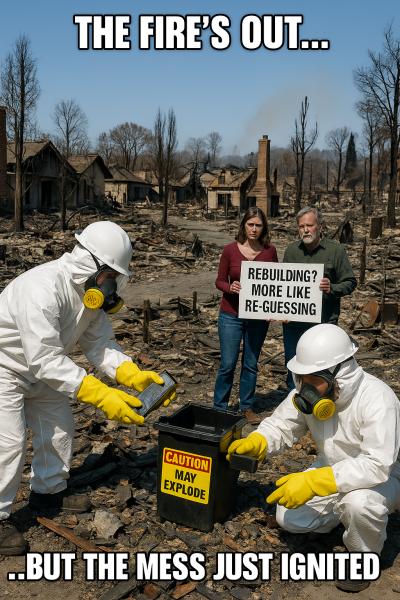

It has been six months since the catastrophic Los Angeles fires destroyed homes, businesses, and entire neighborhoods. The heartache and frustration continue for many people who lost everything in the fire and are trying to rebuild their lives. Even for those whose homes were damaged but not destroyed, renovation is a foreboding task, as insurance coverage and environmental questions come to the forefront.

In my previous article, I described how the EPA was responsible for the first phase of the cleanup, which involved removing hazardous waste, and the US Army Corps of Engineers is currently carrying out the second phase, debris removal.

The EPA’s Response

I previously wrote that the removal of hazardous waste would be a central test demonstrating that the EPA can produce tangible, timely results. The EPA appears to have met this test.

President Trump’s Executive Order called for the EPA to “expedite the bulk removal of contaminated and general debris” from the areas affected by the Los Angeles fires, interpreted to mean that the initial cleanup of hazardous waste had to be completed by February 25th. On February 26th, the EPA announced that it had completed its Phase 1 removal of hazardous waste in record time, under 30 days.

The EPA searched and cleared more than 9,000 properties and disposed of more than 1,000 lithium-ion batteries. The effort required more than 1,500 people, working in nearly 50 teams, many of whom cleared properties by hand, searching for substances including bleach, paint, weed killer, batteries, propane tanks, and asbestos. This was no easy task.

The EPA partnered with the California Department of Toxic Substances, and in a rare instance of Federal State collaboration (particularly “blue” California and the Trump Administration), Yana Garcia, California’s Secretary for Environmental Protection, thanked Secretary Zeldin for “the EPA’s historic collaboration with the California Department of Toxic Substances to achieve this significant milestone.”

A Unique Challenge

California was an early adapter of green technologies including solar panels, electric vehicles and the huge wall-mounted panels that come with them, subsequently, the number of lithium-ion batteries recovered in the LA fires far exceeded that found in other disaster recovery efforts (16 times the number of batteries than in the 2023 Maui wildfires).

California was an early adapter of green technologies including solar panels, electric vehicles and the huge wall-mounted panels that come with them, subsequently, the number of lithium-ion batteries recovered in the LA fires far exceeded that found in other disaster recovery efforts (16 times the number of batteries than in the 2023 Maui wildfires).

Removal of lithium-ion batteries presented a considerable challenge. Lithium-ion batteries, when overheated, are highly flammable and might rekindle and explode, days to months after the initial overheating. Removing the batteries is a labor-intensive process, involving mapping an area and sifting through the wreckage. For electric vehicles, workers had to disconnect the voltage cables to the airbags and seatbelts, saw off the tops of the cars, and flip the cars over to access the battery packs underneath. Wall-mounted battery storage systems weighing over 200 pounds had to be disassembled at processing sites. The batteries were soaked in a brine solution to reduce their stored energy and mitigate the risk of fire, then crushed and moved to a waste disposal facility.

US Army Corps of Engineers

The US Army Corps of Engineers began Phase 2, which involves the removal of the “ash footprint,” the area where burned debris settled after the fire in late February. That footprint includes walls and chimneys, burned appliances, cars, furniture, foundations, and segments of the driveway where ash and debris fell. They removed up to six inches of soil, sent to 17 landfills and recycling centers across California.

The issue of soil removal is a matter of controversy. California Governor Gavin Newsom has stated that removing six inches of soil is not enough and has asked FEMA to test the remaining soil for contaminants, as was done in previous wildfires. Some scientists and community members agree and are calling for more testing. However, FEMA states that they revised their approach to soil testing in 2020 because they discovered that contamination deeper than six inches was pre-existing (not a result of the fire) and is therefore unnecessary for public health protection.

There have also been issues of improper dumping. In late February through March, outsourced federal contractors improperly dumped truckloads of asbestos-tainted waste, a hazardous waste, into a nonhazardous waste landfill, where workers were not wearing respiratory protection. It is unclear whether any enforcement action has been taken against the contractors or landfill owners, raising concerns among environmental groups and residents about the safety of the landfills, which are often located in residential areas.

A Homeowner’s Nightmare

Los Angeles homeowners faced a difficult decision: by April 15th, they had to decide whether to sign up for the free cleanup offered by the US Army Corps of Engineers or to have the cleanup completed by private contractors. More than 70% of the property owners opted for the free government program, while approximately 2,000 property owners hired private contractors. Roughly half of these homeowners did not meet the June 30 deadline for clearing their properties.

Why did people opt out?

- Concerns (distrust) about the quality and completeness of the federal response. Homeowners worried that the federal approach might leave behind unsafe levels of toxic substances, and some wanted to clean beyond the “ash footprint.”

- Greater control and flexibility, allowing for a more customized and thorough cleanup.

- Insurance and financial considerations. Some homeowners prefer using their insurance directly to negotiate terms or have policies that inadequately cover government cleanup.

- Homeowners feared the federal approach would be slow and inefficient.

For those who opted out,

“There’s no guidelines for moving back. There’s no guidelines for what you should be looking for. There’s no guidelines telling you who to call or regulate testing. It’s like – it’s a Wild West out there with the testing, with the remediation companies. People are just grasping at straws with no guidance from the government.” -Lynn McIntyre, burn area resident

In many cases, insurance companies do not cover testing inside homes, so the homeowner must pay the cost. A critical milestone is for local governments to establish guidelines to assist homeowners and insurance companies.

For those who opted in,

“Two of the ten Army Corps-remediated homesites in Altadena still had toxic heavy metals in excess of California standards for residential properties — including one where lead levels were more than three times higher than the state benchmark” – Los Angeles Times

Although the State of California is urging federal officials to reconsider their decision not to pay for testing, neither the State nor the city of Los Angeles has committed to covering the cost of testing.

For those rebuilding, the road ahead is long, likely to take years. The EPA met its objectives with the initial cleanup, but it is too early to judge the performance of the Army Corps of Engineers. From a broader perspective, all levels of government agencies need to view the Los Angeles fires as a test case for rebuilding more efficiently in the face of natural disasters. As the intensity of hurricanes, floods, and fires increases, we need to develop better procedures and find ways to shorten the recovery time.

Sources: President Trump came through for Los Angeles

How LA removed one million pounds of lithium ion batteries

Federal Contractors Dumped Wildfire Asbestos Waste

Fire Debris Clearance: How to decide

California wildfire cleanup crews tackle toxic waste, risk of exploding batteries