Dicamba is a widely used herbicide for weed control, on which many soybean and cotton farmers depend. Under the law, an herbicide is approved if it

“will not generally cause unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.”

Dicamba is involved in an ongoing policy tug-of-war over whether it satisfies the criteria for “unreasonable adverse effects” and represents an overall redefinition of acceptable risk, which changes with each new Administration.

Dicamba

What makes Dicamba particularly interesting is that it has been widely used since 1967 on commercial and residential turf, as well as in forestry, golf courses, lawns, and in agriculture, including corn, cotton, soybeans, sugarcane, and wheat crops. The controversy over Dicamba is over a narrow application of its use.

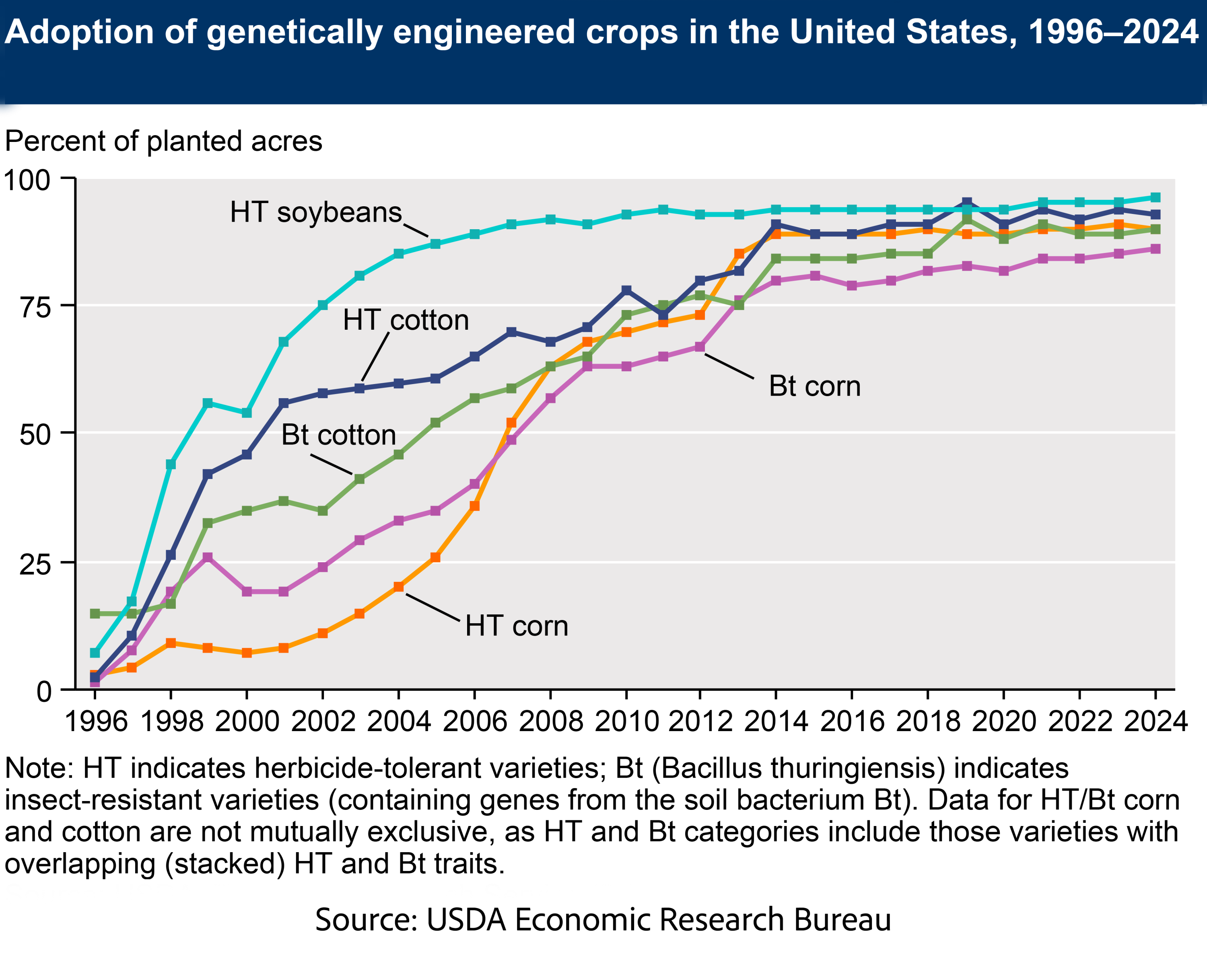

As discussed previously, in 1996, manufacturers introduced seeds that were genetically engineered to be resistant to specific herbicides,  including Dicamba. Dicamba does not damage crops grown from these GMO seeds but kills weeds growing near the crops. This is enormously beneficial to farmers, increasing their crop yields and efficiency. These seeds were rapidly adopted across the US, primarily for soybeans, cotton, and corn. Today, over 90% of these crops in the US are the product of genetically engineered seeds.

including Dicamba. Dicamba does not damage crops grown from these GMO seeds but kills weeds growing near the crops. This is enormously beneficial to farmers, increasing their crop yields and efficiency. These seeds were rapidly adopted across the US, primarily for soybeans, cotton, and corn. Today, over 90% of these crops in the US are the product of genetically engineered seeds.

Dicamba Drift

One of the major controversies surrounding the use of Dicamba is its ability to “drift” from where it is sprayed, damaging crops, as well as desirable plants, bushes, and trees in neighboring fields that are not grown from genetically engineered seeds. This is particularly a problem in hot weather and with temperature inversions [1], which can cause Dicamba to vaporize and become suspended near the ground surface, subsequently moving into neighboring fields. Drift has pitted neighbors against neighbors and is central to several lawsuits.

Another issue is over-reliance on Dicamba, as weeds become increasingly resistant, a phenomenon that has also occurred with other herbicides, such as glyphosate, and antibiotics in microbes. There are also concerns that the EPA understated its effects on bees and other pollinators, which critics believe could lead to significant losses in honey production.

The Regulatory Picture

Under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), all pesticides and herbicides seeking EPA approval for use in the US must demonstrate that the product

“will not generally cause unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.”

The law goes on to say that “economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of the pesticide” may be considered. This sets up a regulatory tug-of-war and is why each Administration can switch its interpretation of the law.

Before 2016, Dicamba use was restricted to mixing it in the soil before planting a crop; however, in 2016 and 2017, the EPA approved spraying three dicamba products “over-the-top (OTT)” for growing genetically engineered soybeans and cotton. This change was approved because spraying Dicamba on the growing plants is the most effective method for killing weeds on these crops. In 2018, the EPA extended that approval for an additional two years.

Before the 2016 approval, the EPA prepared a draft risk assessment on Dicamba’s OTT use, which was updated in 2022. The EPA found no dietary, residential, or post-application risks of concern and identified only an occupational hazard for workers who might inhale the product. Nor did the EPA find evidence that Dicamba was associated with an overall risk of cancer or any specific type of cancer, based on animal studies and the Agricultural Health Study, a study of 41,969 private and commercial pesticide applicators in Iowa and North Carolina. The primary environmental concern was the potential harm to neighboring plants from Dicamba drift and volatilization.

For the last five years, the approval of Dicamba for genetically engineered crops has ping-ponged back and forth due to lawsuits and EPA action. The issue has not centered on human health, but on the effects of Dicamba drift on the environment. After its initial approval, its use was canceled in June 2020 due to a lawsuit. The EPA reapproved it in October 2020, but another lawsuit resulted in its cancellation in 2024. On July 23, 2025, the EPA announced a proposal essentially reversing its 2024 decision to disallow Dicamba’s use.

The EPA included provisions in its proposed approval to protect workers’ health, requiring applicators to wear personal protective equipment, including NIOSH-approved respirators. To protect against drift, it set maximum application rates, prohibited aerial applications, established buffer zones, and implemented temperature-dependent restrictions on application.

Weeds

Weeds “quickly establish in, protect, and restore soil that has been left exposed by natural and human-caused disturbances.” On the other hand, weeds are the most costly type of pest to farmers, causing greater yield loss and adding significantly to farmers’ costs than insect pests, crop pathogens, or pests such as rodents, birds, and deer. Weeds compete directly with crops for light, nutrients, moisture, and space, releasing natural substances that inhibit crop growth, hosting pests or pathogens, and contaminating crop harvest. Weeds result in higher costs for farmers, since they may need to use more labor-intensive (manual) weed control, which results in more soil disturbance and erosion.

With 500,000 soybean farmers in the US, we rank first in global soybean production. Soybeans are grown on approximately 87 million acres, with 80 percent of farms concentrated in the Midwest. Weed control is crucial for soybean farmers, with one study finding that if not controlled, weeds could destroy up to 50 percent of our soybean yield.

Cotton is another major US crop, with approximately 16,000 farms producing nearly 20 million bales of cotton. We are the largest global exporter of cotton. Cotton, in its earliest stages of growth, is slow-growing, making it even more susceptible to weeds than soybeans

The EPA moved quickly because, without herbicides, yields would fall, leading to higher prices and, in some instances, farm failures.

The Dicamba debate is less about a single herbicide and more about how we define risk, responsibility, and regulatory consistency in American agriculture. As administrations pivot, so too do the standards that determine what is considered environmentally safe. The result is a chaotic patchwork of shifting interpretations, frustrating farmers, emboldening environmentalists, and leaving the EPA in the crosshairs of both. Until we establish a more stable regulatory framework that can withstand political turnover, the cycle of litigation, cancellation, and reapproval will persist, rendering our pesticide policies a perennial game of administrative whack-a-mole.

[1] a weather phenomenon where a layer of warm air sits above a layer of cooler air near the Earth's surface, reversing the normal temperature pattern.