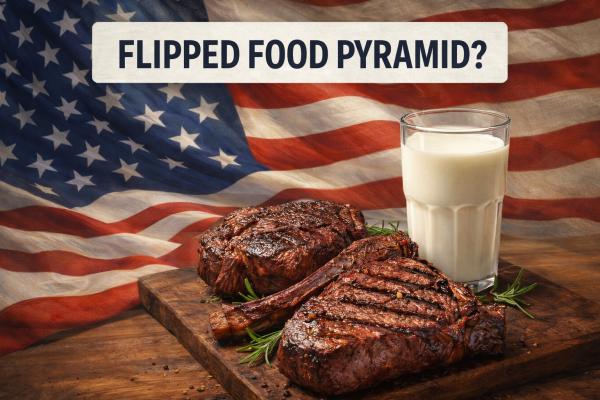

At a glance, these guidelines are a major reset from the last iteration. Less “MyPlate,” more a flipped, old-school food pyramid. Protein, full-fat dairy, and fats are now right up top, sharing center stage with fruits and vegetables. Whole grains, meanwhile, have been pushed way down to the narrow bottom tip. The visual message is basically: eat them, but don’t build your diet around them.

Calling out highly processed foods? Huge win. The new guidance’s core themes are loud and clear:

- Prioritize real, minimally processed foods, including a mention for fermented veggies, an interesting nod towards the importance of gut health

- Cut back on added sugar and ultra-processed foods

- Eat more protein

- Stop fearing full-fat dairy

The last two points are where things start to get interesting and controversial.

A Very American Departure

What really jumps out is how far these guidelines drift from the international consensus. Most global bodies continue to emphasize plant-forward eating, limits on red meat, and caution around saturated fat for both heart health and environmental reasons.

The US seems to be saying: load up on animal protein, including red meat, and favor full-fat over low-fat versions of milk, cheese, or yogurt.

Officially, the new guidelines retain the long-standing recommendation to limit saturated fat to less than 10% of total calories. But good luck with that, given this sits alongside encouragement to eat more animal fats.

On dairy, I’ll give them a partial pass. There is growing evidence that saturated fat behaves differently depending on the food matrix (the whole food it is found within), and that dairy fats, especially in fermented products like yogurt, don’t appear to raise cardiovascular risk in the same way as saturated fats more generally. Calcium, fermentation, and the overall structure of dairy foods may blunt some of the harm. That’s a reasonable scientific debate.

But reasonable debate is not the same thing as making full-fat dairy a flagship symbol of national dietary policy.

The Red Meat Problem

Where this really starts to wobble is the effective greenlighting, almost an “eat as much as you want” framing of red meat. That’s not just a nuance shift; that is a seismic break from decades of cardiovascular guidance.

The American Heart Association has already pushed back, warning that higher red meat intake, especially when paired with sodium-heavy seasoning and cooking methods (I’m looking at you, grillers out there), could worsen heart disease risk. Their stance hasn’t changed: prioritize plant proteins, seafood, and leaner options.

And handwaving that away with “the AHA is just a Big Sugar puppet” doesn’t cut it. That’s lazy and disingenuous. You don’t need a conspiracy theory to explain the AHA’s concern over five decades of cardiovascular epidemiology.

If we’re going to talk about influence, it’s at least worth acknowledging that beef has one of the strongest lobbies in American agriculture.

Beef tallow and the politics of fat

Which brings us to the beef tallow shout-out. That move tracks closely with the views of Robert F. Kennedy Jr., who has been very vocal about rehabilitating saturated fats and animal foods under the “Make America Healthy Again” banner; a detail that feels more cultural than scientific. But explicitly backing animal fats like butter and beef tallow over seed oils feels less like evidence-based guidance and more like taking a side in a nutrition culture war.

Protein: Do We Really Need More?

Another emphasis that’s trendy but not fully supported is the heavy push toward higher protein intake.

Most Americans already get more than enough protein, typically landing around 13–16% of total calories. That’s well above minimum requirements. Higher protein can be helpful for older adults, weight loss, and muscle preservation.

Scaling up red meat consumption, the hardest-to-scale protein, seems incompatible with feeding a growing population sustainably. Emissions, land use, and water consumption all add up. You don’t have to be a climate activist to notice the tension between “eat more beef” and long-term food system resilience. Moreover, as a blanket national priority, protein’s new role feels misplaced when fiber intake, dietary quality, and the dominance of ultra-processed foods remain bigger problems.

It does raise a fair question: are we quietly drifting toward low-carb ideology? Not explicitly – the guidelines still acknowledge whole grains as beneficial, just no longer foundational. But it’s telling that keto and carnivore influencers are already celebrating this as validation.

Alcohol: Clearer Science, Vaguer Guidance

The guidelines quietly move away from specific daily limits (“one drink for women, two for men”) toward a vague “drink less.” While that aligns with growing evidence that no amount of alcohol is truly risk-free, swapping numbers for vibes isn’t exactly a triumph of clarity.

Will This Actually Matter?

Here’s the reality check: if you genuinely follow these guidelines—eat plenty of fruits and vegetables and adequate protein, keep carbs relatively modest with an emphasis on whole grains, you will be fine. Humans are remarkably adaptable across a range of macronutrient ratios.

And honestly, the strongest, least controversial message here is the one we’ve known all along: eat less ultra-processed junk. But let’s be real:

- Most people don’t follow dietary guidelines.

- Blaming previous guidelines for America’s health crisis ignores the food ecosystem, the convenience culture, and other healthy behaviors.

- And telling people to cook more whole foods sounds great… until you try doing it on a 9-to-5 schedule with limited time, money, or access.

The Real Question

My concern isn’t that “this will destroy public health.” It’s simpler. Why is the US so far out of step with global scientific consensus, especially on red meat and saturated fat, when the most solid, defensible advice didn’t require that swing at all?

Is this evidence-based recalibration? Or is it ideology, politics, and backlash dressed up as nutrition science? If we’re going to rewrite national dietary guidance, the bar should be higher than vibes, influencer applause, and culture-war optics.

First thoughts. Let’s see where this lands.