In June 1812, Napoleon invaded Russia, leading his Grande Armée of about 680,000 men. The Russians, avoiding confrontation, retreated eastward while employing a scorched-earth policy that left the advancing French army without food or shelter. After a bloody but indecisive victory at Borodino, Napoleon entered a burning Moscow in September, only to find it abandoned and set aflame on orders from its governor. With winter closing in and Alexander refusing peace, Napoleon was forced to withdraw in October. Harried by Cossacks, starvation, and subzero temperatures, the Grande Armée disintegrated as it struggled westward. Of the massive force that had crossed into Russia, barely 75,000 returned. The campaign remains one of the greatest military disasters in history.

Centuries later, engineers and scientists would find new ways to map and analyze the biological forces that shaped this catastrophe. One man would turn Napoleon’s doomed march into one of history’s most powerful visual lessons.

Mapping a Catastrophe

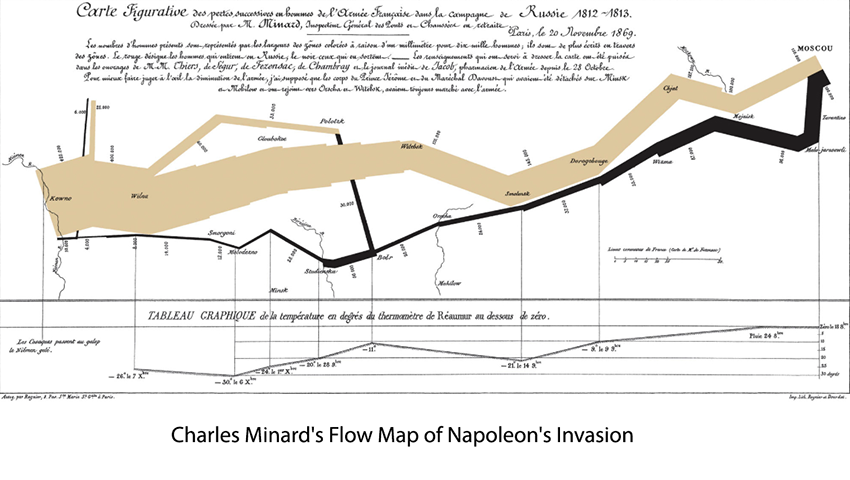

Charles Joseph Minard was a French civil engineer celebrated for pioneering the use of flow maps to visually represent complex statistical and geographic data. His flow maps used line width to represent quantities in motion—such as traffic, trade, or military forces—making relationships between numbers immediately visible. His map of Napoleon’s entry and retreat from Moscow, done when Minard was 80, depicts the catastrophic losses of Napoleon’s Grande Armée during its invasion and retreat from Russia.

The orange and black bands trace the army’s advance and withdrawal, their width shrinking as soldiers died from battle, starvation, disease, and freezing temperatures. It integrates troop numbers, distance, temperature, latitude and longitude, direction of march, and dates into a single visual narrative – it is an infographic masterpiece of data storytelling.

Yet behind Minard’s elegant lines lay a biological mystery that science would only begin to unravel two centuries later.

When Napoleon’s Grande Armée limped out of Russia in the winter of 1812, most of Europe believed it had been undone by snow, starvation, and typhus. The belief fit the evidence of the time: the soldiers were covered in lice, known carriers of typhus, and the symptoms of fever, rash, and delirium matched those of the disease. For two centuries, historians repeated that explanation; however, the corpses left behind carried a different microbial record of what really happened.

Uncovering a Microbial Truth

Early molecular studies appeared to confirm the historical account, detecting traces of Rickettsia prowazekii (the typhus bacterium) and lice on soldiers’ remains from mass graves near Vilnius, Lithuania, a major stop along the retreat.

However, a new study re-examined the soldiers’ remains using a technique that sequences fragments of ancient DNA directly from human teeth, which preserves blood-borne pathogens.Researchers extracted DNA from 13 soldiers interred in that mass grave, searching for ultra-short, ancient DNA fragments of microbial DNA.

The results were surprising. While finding no traces of Rickettsia prowazekii or Bartonella quintana, the cause of “trench fever,” the researchers found two diseases spread by lice and contaminated food and water, Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C, the cause of paratyphoid fever, and Borrelia recurrentis, which causes relapsing fever. Needless to say, there is significant overlap in the digestive symptoms of typhus, paratyphoid fever, and relapsing fever, and without cultures or today’s DNA sequencing, they are impossible to distinguish from one another.

J.R.L. de Kirckhoff, a physician who served in Napoleon’s army, reported widespread diarrhea, fever, and jaundice, all consistent with paratyphoid fever. He noted that soldiers often drank the brine from barrels of salted water to quench thirst, likely ingesting bacteria from contaminated water sources. The new genetic findings overturn long-standing historical assumptions. The biological devastation accompanying Napoleon’s retreat was not primarily due to typhus, but to a complex mix of enteric (gut-based) and louse-borne infections.

When the Body Became the Battlefield

As Napoleon’s Grande Armée advanced deeper into Russia, its greatest adversaries were not enemy soldiers but biology itself. The prolonged march of more than 1800 miles, combined with starvation, sleeplessness, and subzero temperatures, drove the men into physiological exhaustion. In such conditions, the immune system falters: caloric deprivation depletes vital nutrients, such as zinc, iron, and vitamin C, all crucial for immune cell production. Frostbite, hypothermia, and malnutrition diverted the body’s remaining energy toward basic survival, leaving soldiers defenseless against infection.

What began as scattered outbreaks of fever and diarrhea soon spread like wildfire through the ranks, as weakened immune systems turned the human body into fertile ground for microbes. Contaminated food and water, lice infestations, and open wounds created a perfect storm of infection. Disease does not simply accompany war; it can become a combatant.

An Army Marches on Its Stomach—and Retreats on Its Immune System

Napoleon famously declared that “an army marches on its stomach,” and indeed, supply and sustenance determine the forward momentum of any campaign. Yet the retreat from Moscow revealed an inverse truth: an army may retreat on its immune system. Logistics might move men across maps, but immune resilience determines whether they survive long enough to return. The Grande Armée’s immune collapse transformed a military retreat into a microbial rout. The soldiers’ bodies, stripped of their natural defenses, became unarmored hosts to pathogens that moved faster than any cavalry. In the end, the immune system proved as decisive a factor as any general’s strategy.

Charles Minard’s haunting flow map of Napoleon’s 1812 campaign visualizes the biological unraveling of an empire. The dwindling line that narrows across Russia is not just a record of battle casualties, but a chronicle of starvation, disease, and immune collapse. The study of ancient DNA has given voice to the microbes that history forgot, revealing that Napoleon’s defeat was as much microbial as military.

Source: Paratyphoid Fever and Relapsing Fever in 1812 Napoleon’s Devastated Army Current Biology DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.09.047