I'm a big fan of birds. If you watch them for long enough, you will see more than their colors, sizes, and shapes. They also have distinct personalities.

(That said, years ago I temporarily became less of a fan when one of them turded on my pizza. Enough of that.)

Some of them are also "tricky." They fool you into thinking that they are a beautiful blue color, but this is just an illusion. (More on that later.)

Black-capped chickadees are fearless. They will eat out of your hand if you stand still. Catbirds don't scare easily either, and they are rather inquisitive. If you leave your door open, it is not impossible that you will find a catbird sitting on your kitchen counter. I found this out the hard way. (Getting it out of there was rather challenging.)

Northern Cardinals are both timid and polite. It does not take much more than the sound of a cotton ball falling on a Tempur-Pedic mattress to scare them away. And, if other birds are on the feeder, cardinals will sit calmly nearby and wait for them to finish. Then they hop on and start to feast. New Yorkers should take etiquette lessons from cardinals.

Blue jays are much more like New Yorkers in line at Trader Joe's. They dive bomb the feeder with their huge blue wings fully extended, screaming at the other birds, which promptly get the hell out of the way.

Left to right: Black-capped chickadee, cardinal, bluejay.

But there are a couple of differences between blue jays and New Yorkers. New Yorkers can't fly [1], and, with the exception of the guys in Blue Man Group, we are not blue.

But neither are the blue jays. They obviously look blue, but here is something that you probably don't know: There is no blue pigment in their feathers.

So what’s really going on with all that blue?

If you grind up the wing of a cardinal, the resulting powder will be red. If you do the same with a blue jay feather, the powder will be brown. You can see the same effect by simply turning around a blue feather.

This effect is not unique to blue jays. Blue birds are not really blue. They do not have any blue pigment. Instead, they use a very cool trick called light scattering. It is somewhat similar to how a prism works. But nature uses a trick that is much more complex.

How does this work? Blue wings contain tiny pockets made of air and a protein called keratin [2]. These pockets are so small that they fall into a group of minuscule structures called nanoscale structures, which range in size from microscopic to molecular. The tiny pockets are even smaller than the wavelength of visible light, which is exactly why they work (see below).

For perspective, here are examples of some very small entities, measured in nanometers (nm):

Grain of sand- 500,000 nm

Thickness of a human hair- 70,000 nm

Red blood cell- 7,000 nm

Wavelength of visible light- 380-750 nm

Feather nanostructures - Several hundred nm

Viruses- approx. 20-250 nm

Gold atom- 0.14 nm

Note that the feather nanostructures are similar (or even smaller) than the wavelength of visible light. This is no coincidence.

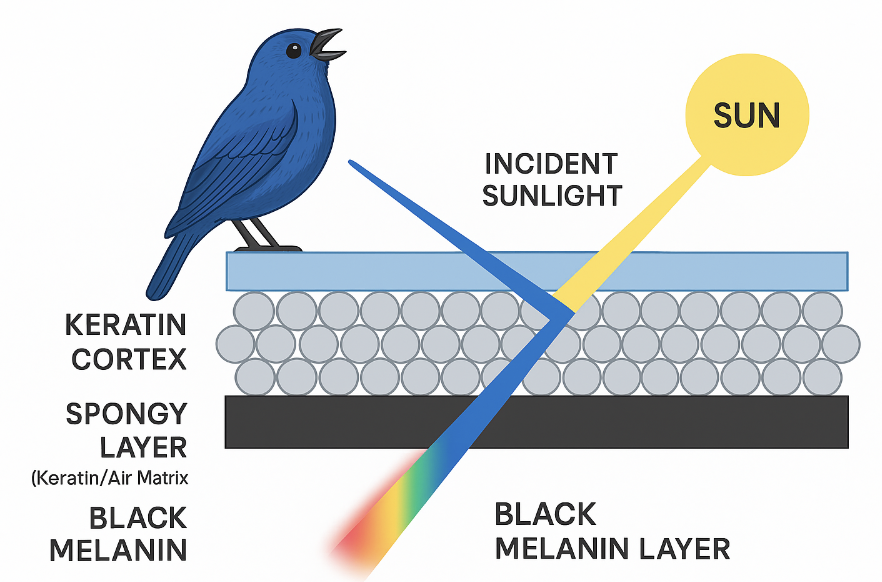

Figure 1 explains why you see blue in feathers.

Figure 1. Scattering of light by bird feathers.

Visible light strikes the feathers and encounters the keratin-air nanostructures. The size of the nanostructure matches that of the wavelength of blue light. So, while all of the other colors pass through the feather, the blue does not. It is reflected, so you see blue.

This is why ground-up feathers turn brown. Once the nanostructures are destroyed, you see the bird's true colors. This is also why you do not see blue when the feather is turned around. The "prism" is now on the wrong side.

Nature’s palette doesn’t need paint. Color me impressed.

Notes:

[1] This is more literal than you might think. One flight in or out of LaGuardia Airport, and you will understand

[2] Keratin is the same protein that makes up hair and fingernails