The Biggest Loser, inspired by a gym post in which someone pleaded, “I need the help of a personal trainer to save my life,” ran for 18 seasons and grew into a global franchise. The show featured obese participants competing in diet and exercise challenges, facing eliminations based on total weight loss, with $250,000 awarded to the “biggest loser.” All with the promise of restored health, though their mental well-being deteriorated with each episode. A recent documentary has since exposed the grim backstage reality and the lasting physical and emotional scars many participants carried.

The format combined weigh-ins, fat measurements, pairings, and punishing workouts often laced with humiliation. Diets were officially prescribed at 1,400–1,500 kcal/day, but many contestants reported being pushed to just 800 kcal — with no medical supervision. Contestants also faced “temptation trials,” in which they had to choose between indulging in high-calorie foods for a strategic advantage or resisting at the risk of elimination.

To increase calorie burn, caffeine capsules were widely used, even though the show’s doctor had banned coffee. This was especially concerning, as caffeine supplements are not recommended for individuals with high blood pressure; studies show they can temporarily raise blood pressure and potentially trigger cardiovascular complications.

The program was not a health initiative but televised torture, designed solely to entertain at the expense of participants’ physical and emotional well-being.

However, the show’s fatphobic stance did not stem solely from its creators or “health professionals” alone, but reflected the prevailing attitudes of the time. Before obesity was studied scientifically, the common belief was that obese individuals were lazy and lacked willpower. The producers capitalized on this prejudice — a mindset that, unfortunately, still echoes today in the discourse of many fitness coaches.

Two positive aspects emerged from The Biggest Loser. First, numerous findings from the show’s participants continue to inform research on weight loss in obese patients, particularly regarding metabolic adaptation and the physiological challenges of maintaining weight. Second, and perhaps more importantly, the series, unintentionally, helped dismantle the simplistic and mistaken notion that obesity is a choice.

It highlighted the profound physiological changes that make both losing weight and keeping it off extraordinarily difficult, demonstrating that the body’s response to weight loss involves complex hormonal and metabolic adaptations that persist long after the cameras stop rolling.

The Science of The Biggest Loser

In 2012, eight years after the first season, researchers conducted an observational study to assess whether contestants on The Biggest Loser preserved their muscle mass (fat-free mass, FFM) and minimized metabolic slowdown during weight loss.

The study followed 16 contestants (9 women and 7 men) for 30 weeks, where they trained vigorously for 90 minutes six times a week, with up to three additional hours of exercise daily. Food intake was not monitored, but participants were advised to consume about 70% of their baseline intake, roughly 1,400 kcal/day.

With an average BMI of 49.4 kg/m² and a weight of 149.2 kg, of which roughly 49% was body fat, the participants were severely obese. They lost about 15 kilograms in the first six weeks, primarily fat, and by week 30, the mean weight loss reached around 40% of baseline.

Given this enormous weight loss, the Resting Metabolic Rate (RMR) — the energy expended at rest to meet our resting needs- was expected to drop by about 175 kcal. Surprisingly, it fell far more, by 664 kcal, a 25% decrease. This demonstrates metabolic adaptation, where our resting needs decline more than expected as our body seeks to maintain its “baseline” weight and end the continued weight loss. Metabolic adaptation suggests that an obese person needs to continuously monitor their diet and maintain high levels of physical activity to maintain significant weight loss.

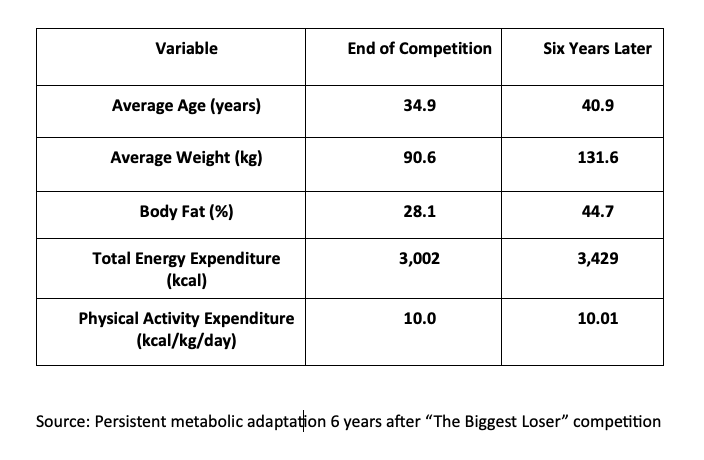

This conclusion was reinforced by a 2016 study into whether metabolic adaptation persisted years after the competition and whether it was linked to weight regain. Researchers recruited 14 of the 16 contestants and reassessed their resting metabolic rate and body composition six years later:

All but one regained weight; five reached or exceeded their starting weight. The 40 kg gain over six years was not the study’s most concerning finding; that distinction goes to resting energy expenditure. While modeling predicted approximately 2,400 kcal/day after six years, actual measurements averaged just 1,903 kcal/day — 497 kcal/day below baseline, significantly lower than expected for participants’ body composition and age.

Metabolic adaptation is persistent, proportional, and pronounced. On average, participants maintained an 11.9 kg loss compared to baseline, still a positive outcome, but one that highlights how long-term weight maintenance requires a constant battle against metabolic adaptation.

The Complexity of obesity

Obesity is a complex, chronic disease affecting more than a billion people and increasing the risk of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cardiovascular disease, and certain types of cancer.

Genome-wide association studies (GWAS), a robust methodology for identifying genetic variations linked to specific traits and diseases, have identified hundreds of variants related to BMI, food preferences, and metabolism. Yet, these explain only about 5% of individual variability in weight. The interactions of genes, influenced by diet, smoking, and physical activity, play a substantial role.

Energy balance depends on complex hormonal, neural, and sensory signals between the brain, adipose tissue, and the gastrointestinal tract. The stomach signals fullness through distension, triggering neural feedback that reduces appetite regardless of calorie intake. Gastric motility, which affects stomach emptying, also influences satiety, and disruptions are associated with obesity and increased hunger.

Hormones further regulate food intake: ghrelin stimulates appetite, while GLP-1 promotes satiety.

Adipose tissue also secretes leptin and adiponectin. Leptin reflects energy stores and helps regulate body weight by reducing hunger and increasing satiety, but resistance to this hormone is common in obesity. Adiponectin, in turn, supports weight homeostasis, improves insulin sensitivity, and promotes fatty acid oxidation, yet its levels are reduced in obesity and closely linked to visceral fat.

Psychological factors, including stress and trauma, can predispose individuals to obesity, where food often functions as a coping mechanism, leading to repeated reliance and gradual weight gain. High-calorie or sugary foods become especially compelling during stressful periods. Body dissatisfaction and low self-esteem drive shame, guilt, and social withdrawal, along with social stigma and discrimination, promoting emotional eating and increasing the risk of mood disorders.

Once established, obesity is reinforced by hormonal, structural, and psychological changes. The idea that obesity is simply a matter of choice or willpower is unscientific and prejudiced, suitable only for self-help books or commercialized courses.

Redefining Obesity?

In 2024, researchers began questioning BMI, the tool we still rely on to classify obesity.

Grannell and Le Roux argued that while BMI is useful for tracking population trends, it has obvious flaws. It overlooks people with a “normal” weight who nonetheless carry dangerous amounts of fat and face high disease risk. They called for a model that goes beyond calories in and out, incorporating genetics, pathophysiology, and appetite regulation.

A year later, a commission of experts proposed objective criteria for diagnosing obesity:

- Clinical obesity: a chronic, systemic disease characterized by functional alterations in tissues, organs, or both due to excess adiposity. This condition can severely damage target organs, leading to potentially disabling and life-threatening complications.

- Preclinical obesity: a state of excess adiposity with preserved tissue and organ function, presenting a variable—but generally elevated—risk of progressing to clinical obesity and other chronic non-communicable diseases.

The commission emphasizes that BMI should only be used at the population level and always supplemented by anthropometric measurements, such as waist circumference. A diagnosis of clinical obesity requires one of two criteria: evidence of obesity-related organ or tissue dysfunction, or significant limitations in daily activities.

Based on the assumption that a high BMI usually reflects high adiposity, one key point of the new definition stands out: whether obesity is classified as clinical or preclinical, some form of intervention should begin, ranging from targeted lifestyle changes to medical care as needed. While it is tempting to judge past approaches harshly, it is encouraging to see the scientific community advance toward more accurate, evidence-based definitions — moving beyond BMI and simplistic ideas of willpower or “wrong choices.”

This new framework emphasizes that obesity is a chronic, systemic disease, that stigma hinders effective care, and that addressing it requires both clinical insight and compassion. By reframing the debate, it counters misconceptions on social media and in public discourse while providing a clear path for prevention and treatment. Obesity is no longer a matter of blame.

Sources: Metabolic Slowing with massive weight loss despite preservation of fat-free mass. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism DOI: 10.1210/jc.2012-1444

Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after "The Biggest Loser" competition. Obesity DOI: 10.1002/oby.21538.

Obesity as a disease: a pressing need for alignment. International Journal of Obesity DOI: 10.1038/s41366-024-01582-8

Definition and diagnostic criteria of clinical obesity. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology DOI: 10.1016/S2213-8587(24)00316-4