A few years ago, the nutrition field was shaken when Dr. Hall and colleagues conducted a randomized controlled trial to test whether consuming ultra-processed foods (UPFs) could influence energy intake. To the surprise of many, the answer was yes. In a strictly controlled hospital setting, where all meals were prepared and delivered to participants, those in the UPF group consumed approximately 508 kcal more per day than the control group, resulting in a weight gain of nearly 2 pounds in just two weeks.

Building on these findings, six years later, a different research team, also including Dr. Hall, examined the health effects of a diet rich in UPFs in an environment that “mimicked” real-world conditions, with participants receiving the food at home, aiming to understand how these foods influence intake and health under more typical circumstances.

If you missed the hype surrounding the results, several outlets framed it like this:

“People in the United Kingdom lost twice as much weight eating meals typically made at home than they did when eating store-bought ultraprocessed food considered healthy, the latest research has found.” — CNN

Yet while the study did report this finding, the details and context reveal something far more interesting, which most reports overlook: that challenges the prevailing narrative – depending on their composition, ultra-processed foods can produce beneficial effects.

Is Processing the Problem?

The study compared the health effects of diets based on minimally processed (MPF) and ultra-processed foods (UPF). Both were designed to align with the UK’s EatWell Guide, which categorizes foods into five main groups: fruits and vegetables, starchy carbohydrates, proteins, dairy products, and oils and fats, while providing additional recommendations regarding daily fluid intake, moderate food consumption, and reading nutritional labels.

The researchers evaluated weight change along with cardiometabolic, behavioral, mental, and hormonal outcomes, while also examining the feasibility and acceptability of the behavioral support intervention.

As with Dr. Hall’s prior study, after completing one eight-week diet, participants underwent a short “washout” period with no treatment, then “crossed over” to the other diet for an additional eight weeks. Fifty-five participants, all with a habitual intake of at least 50% of calories from UPFs, completed the study and, by the crossover design, acted as their own “controls.”

Researchers prepared and delivered all meals, snacks, and beverages twice a week, following government guidelines that reduced the amount of saturated fat, added sugar, and salt. Portions provided approximately 4,000 kcal per day, allowing participants to choose how much to consume (ad libitum intake). Unlike typical trials, this study incorporated reformulated, nutritionally enhanced UPFs, such as breakfast cereals, ready-to-eat meals, and plant-based alternatives.

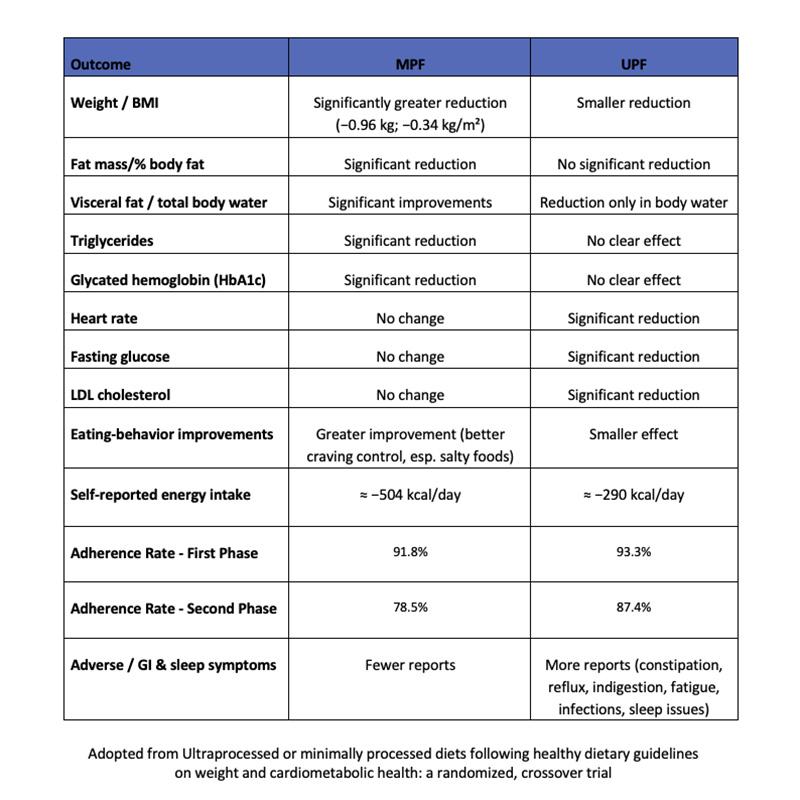

Of the 55 enrolled participants, 50 provided primary outcome data for at least one diet, and 43 completed both phases. After eight weeks, weight loss averaged 2.06% on the MPF diet and 1.05% on the UPF diet. If these results were sustained over a year, estimated weight loss would reach approximately 9–13% on the MPF diet and 4–5% on the UPF diet.

An order effect was observed, with greater weight loss occurring on the diet followed in the first phase.

The authors concluded that eight-week ad libitum diets, following UK guidelines, produced weight loss, with significantly greater reductions on the MPF diet. The MPF diet resulted in larger decreases in fat mass and total body water, whereas the UPF diet reduced body water only, without significantly affecting total adiposity. Several mechanisms might explain the observed differences in weight, including nutritional composition, texture, energy density, and rate of ingestion for the two diets.

UPFs, even when reformulated, are hyperpalatable with more pronounced flavors, which may stimulate consumption. Although appetite ratings were similar between the diets, taste and palatability scores were significantly lower for the MPF diet. This difference may have influenced eating behavior, as some participants abandoned the MPF diet, while none abandoned the UPF diet.

If we were to ignore the limitations highlighted by the authors, we might likely conclude, similar to CNN, incompletely and lacking a critical perspective. Fortunately, that will not be the case.

Context Matters: Unpacking the Study’s Limitations

The study has significant limitations. First, the sample consisted predominantly of highly educated women without dietary restrictions or intolerances, which limits the applicability of the findings to more diverse populations.

Another critical issue is the carryover effect. Because participants underwent multiple interventions, it is difficult to determine whether outcomes reflected the diet or the “ordering” of the experience. This is especially relevant since weight loss was consistently greater on the initial diet followed, regardless of whether it was MPF or UPF.

The study design also introduced several potential sources of bias. It was not blinded, and participants received weekly support calls from researchers, which may have influenced both food intake and responses to subjective questionnaires. In addition, the uncontrolled, “free-range” setting makes it unclear whether participants consumed only the provided foods. Although most submitted food diaries, recall errors, or attempts to offer “desirable results” may have occurred.

One nuance the researchers did not emphasize is that, despite the free-range design, all meals were delivered directly to participants’ homes. This convenience may have biased adherence, but it can also be viewed as a study “strength,” since home delivery increasingly reflects how younger generations' real-world eating.

Adherence to the MPF diet was lower than to the UPF diet, raising concerns about long-term sustainability. While MPF diets resulted in greater short-term weight loss, higher dropout rates could offset the long-term benefits and increase the risk of weight regain.

Overall, the trial extends Hall’s 2019 controlled laboratory study into a real-world setting: unblinded, less strictly regulated, but arguably more reflective of modern dietary habits.

A crucial distinction is that the study did not aim for weight loss, and participants were not placed in a caloric deficit. Instead, the objective was to assess the health effects of freely consuming MPF and UPF diets, both designed to follow the UK’s recommendations.

Even under these conditions, the presumed addictive and hyperpalatable effects of UPFs did not manifest. Participants still lost weight and showed reductions in fasting blood glucose and LDL cholesterol, two key biomarkers of diabetes and cardiovascular disease. These outcomes likely reflect that the UPFs provided were nutritionally balanced and healthier than typical industrial products.

Choosing MPF foods over UPFs, even when both are nutritionally balanced, may promote weight loss due to their lower energy density, slower eating pace, varied textures, and other factors. However, in terms of long-term applicability, adhering exclusively to an MPF-based diet appears extremely challenging, if not impossible. This limitation can reduce adherence and consistency, ultimately restricting weight loss maintenance or further progress over time.

Based on this study, we can draw an important, if somewhat obvious, conclusion:

While a balanced diet centered on natural, minimally processed foods remains the healthiest option, when ultra-processed foods are included, the diet can still be considered healthy – provided that the proportion of UPFs remains low. Even in cases where the diet contains a high amount of UPFs, something I personally would not recommend, health improvements can still occur, as long as healthier alternatives are selected.

Sources:

Ultraprocessed or minimally processed diets following healthy dietary guidelines on weight and cardiometabolic health: a randomized, crossover trial.Nat Med (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-03842-0